After years of recession and sluggish growth, for many, an economic recovery is the light at the end of the tunnel that will lead to greater employment, higher income and perhaps less inequality. While conventional economic wisdom holds that capitalists should be just as anxious to see recovery as workers, Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler argue that it is actually in capitalists’ interests to prolong the crisis, as their relative power increases in times of stagnation and unemployment. Using U.S. data from the past century, they find that when unemployment rises, capitalists can expect their share of income to rise in the years that follow. Unless society takes steps to decrease unemployment, capitalists are likely to continue to pursue stagnation for their own gain.

After years of recession and sluggish growth, for many, an economic recovery is the light at the end of the tunnel that will lead to greater employment, higher income and perhaps less inequality. While conventional economic wisdom holds that capitalists should be just as anxious to see recovery as workers, Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler argue that it is actually in capitalists’ interests to prolong the crisis, as their relative power increases in times of stagnation and unemployment. Using U.S. data from the past century, they find that when unemployment rises, capitalists can expect their share of income to rise in the years that follow. Unless society takes steps to decrease unemployment, capitalists are likely to continue to pursue stagnation for their own gain.

On May 27th, Jonathan Nitzan will be speaking at the LSE Department of International Relations public lecture “Can Capitalists Afford Recovery?” More details.

Can it be true that capitalists prefer crisis over growth? On the face of it, the idea sounds silly. According to Economics 101, everyone loves growth, especially capitalists. Profit and growth go hand in hand. When capitalists profit, real investment rises and the economy thrives, and when the economy booms the profits of capitalists soar. Growth is the very lifeline of capitalists.

Or is it?

What motivates capitalists?

The answer depends on what motivates capitalists. Conventional economic theories tell us that capitalists are hedonic creatures. Like all other economic “agents” – from busy managers and hectic workers to active criminals and idle welfare recipients – their ultimate goal is maximum utility. In order for them to achieve this goal, they need to maximize their profit and interest; and this income – like any other income – depends on economic growth. Conclusion: utility-seeking capitalists have every reason to love booms and hate crises.

But, then, are capitalists really motivated by utility? Is it realistic to believe that large American corporations are guided by the hedonic pleasure of their owners – or do we need a different starting point altogether?

So try this: in our day and age, the key goal of leading capitalists and corporations is not absolute utility but relative power. Their real purpose is not to maximize hedonic pleasure, but to “beat the average.” Their ultimate aim is not to consume more goods and services (although that happens too), but to increase their power over others. And the key measure of this power is their distributive share of income and assets.

Note that capitalists have no choice in this matter. “Beating the average” is not a subjective preference but a rigid rule, dictated and enforced by the conflictual nature of the system. Capitalism pits capitalists against other groups in society – as well as against each other. And in this multifaceted struggle for greater power, the yardstick is always relative. Capitalists – and the corporations they operate through – are compelled and conditioned to accumulate differentially; to augment not their personal utility but their relative earnings. Whether they are private owners like Warren Buffet or institutional investors like Bill Gross, they all seek not to perform but to out-perform – and outperformance means re-distribution. Capitalists who beat the average redistribute income and assets in their favor; this redistribution raises their share of the total; and a larger share of the total means greater power stacked against others. In the final analysis, capitalists accumulate not hedonic pleasure but differential power.

Now, if you look at capitalists through the lens of relative power, the notion that they should love growth and yearn for recovery is no longer self-evident. In fact, the very opposite seems to be the case. For any group to increase its relative power in society, that group must be able to strategically sabotage others in that society. This rule derives from the very logic of power relations. It means that capitalists, seeking to augment their income-share-read-power, have to threaten or undermine the rest of society. And one of the key weapons they use in this power struggle –sometimes conscientiously, though usually by default – is unemployment.

Joblessness affects redistribution

Unemployment affects distribution mainly through the impact it has on relative prices and wages. If higher unemployment causes the ratio of price to unit wage cost to decline, capitalists will fall behind in the redistributional struggle, and this retreat is sure to make them eager for recovery. But if the opposite turns out to be the case – that is, if higher unemployment helps raise the price/wage cost ratio – capitalists would have good reason to love crisis and indulge in stagnation.

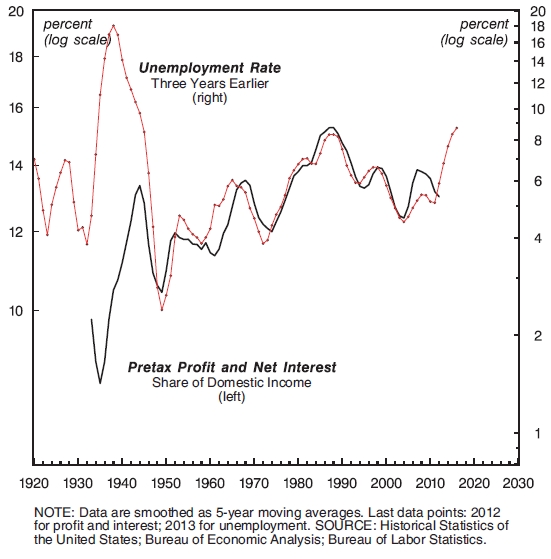

In principle, both scenarios are possible. But as Figure 1 shows, in America the second prevails: unemployment redistributes income systematically in favor of capitalists. The chart contrasts the share of pretax profit and net interest in domestic income on the one hand with the rate of unemployment on the other (both series are smoothed as 5-year moving averages). Note that the unemployment rate is lagged three years, meaning that every observation shows the situation prevailing three years earlier.

Figure 1 – U.S. Unemployment and the Income Share of Capital

This chart does not sit well with received wisdom. Mainstream economics tells us that the two series should be inversely correlated; that the capitalist income share should rise in the boom when unemployment falls and decline in the bust when unemployment rises. But that is not the case in the United States. In this country, the correlation is positive, not negative. The share of capitalists moves countercyclically: it rises in downturns and falls in booms – exactly the opposite of what economic convention would have us believe. The math is straightforward: for every 1 percent rise in unemployment, capitalists can expect their income share three years later to jump by 0.8 percent. Needless to say, this equation is very bad news for most Americans – precisely because it is such good news for the country’s capitalists.

Remarkably, the positive correlation shown in Figure 1 holds not only over the short-term business cycle, but also in the long term. During the booming 1940s, when unemployment was very low, capitalists appropriated a relatively small share of domestic income. But as the boom fizzled, growth decelerated and stagnation started to creep in, the share of capital began to trend upward. The peak power of capital, measured by its overall income share, was recorded in the early 1990s, when unemployment was at post-war highs. The neoliberal globalization that followed brought lower unemployment and a smaller capital share, but not for long. In the late 2000s, the trend reversed again, with unemployment soaring and the distributive share of capital rising in tandem. Looking forward, capitalists have reason to remain crisis-happy: with the rate of unemployment again approaching post-war highs, their income share has more room to rise in the years ahead.

The power of capitalists can also be examined from the viewpoint of the infamous Top 1 percent. Most commentators stress the “social” and “political” problems created by the disproportional wealth of this group, but this emphasis puts the world on its head. Redistribution is not an unfortunate side-effect of growth and stagnation, but the main force driving them.

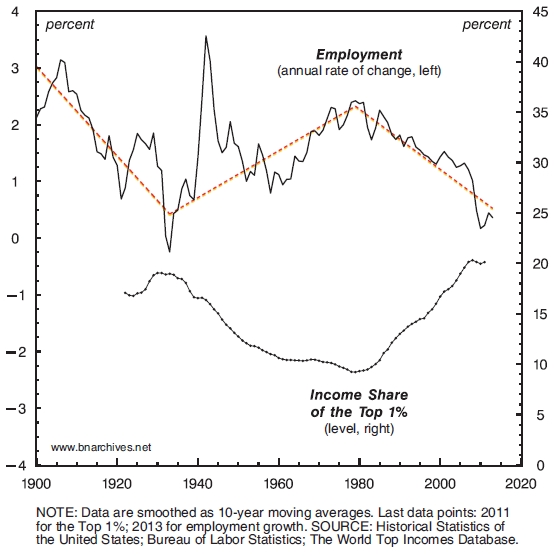

Figure 2 shows the century-long relationship between the income share of the Top 1 percent and the annual growth rate of U.S. employment (with both series smoothed as 10-year moving averages). And as the chart makes clear, the distributional gains of this group have been boosted not by growth, but by stagnation. The overall relationship is clearly negative. When stagnation sets in and employment growth decelerates, the income share of the Top 1 percent actually rises – and vice versa during a long-term boom.

Figure 2 – U.S. Income Distribution and Employment Growth

Historically, this negative relationship can be divided into three distinct periods, indicated by the dashed, freely drawn line going through the employment growth series. The first period, from the turn of the twentieth century till the 1930s, is the so-called Gilded Age. Income inequality is rising and employment growth is plummeting.

The second period, from the Great Depression till the early 1980s, is marked by the Keynesian welfare-warfare state. Higher taxation and public spending make distribution more equal, while employment growth accelerates. Note the massive acceleration of employment growth during the Second World War and its subsequent deceleration brought by post-war demobilization. Obviously these dramatic movements were unrelated to income inequality, but they did not alter the series’ overall upward trend.

The third period, from the early 1980s to the present, is marked by neoliberalism. In this period, monetarism assumes the commanding heights, inequality soars and employment growth plummets. The current rate of employment growth hovers around zero while the Top 1 percent appropriates 20 per cent of all income – similar to the numbers recorded during Great Depression.

So what do these facts mean for America?

First, they make the fault-lines obvious. The old slogan “what’s good for GM is good for America” now rings hollow. Capitalists seek not utility through consumption but more power through redistribution. And they achieve their goal not by raising investment and fueling growth, but by allowing unemployment to rise and jobs to become scarce. Clearly, we are not “all in the same boat.” There is a distributional struggle for power, and this struggle is not a mere “sociological” issue. It is the center of our political economy, and we need a new theoretical framework to understand it.

Second, macroeconomic policy, whether old or new, cannot offset the aggregate consequences of this distributional struggle. Not by a long shot. Till the late 1970s, the budget deficit was small, yet America boomed. And why? Because progressive taxation, transfer payments and social programs made the distribution of income less unequal. By the early 1980s, this relationship inverted. Although the budget deficit ballooned and interest rates fell, economic growth decelerated. New methods of upward redistribution have caused the share of the Top 1 percent to zoom, making stagnation the new norm.

Third, and finally, Washington can no longer hide behind the bush. On the one hand, the concentration of America’s income and assets, having been boosted by large post-crisis bailouts and massive quantitative easing, is now at record levels. On the other hand, long-term unemployment remains at post-war highs while job growth is at a standstill. Eventually, this situation will be reversed. The only question is whether it will be reversed through a new policy trajectory or through the calamity of systemic crisis.

On May 27th, Jonathan Nitzan will be speaking at the LSE Department of International Relations public lecture “Can Capitalists Afford Recovery?” More details.

This article was originally published in Frontline on 16 April, and is based on the paper: Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, ‘Can Capitalists Afford Recovery? Economic Policy When Capital is Power’, Working Papers on Capital as Power, No. 2013/01, October 2013, pp. 1‑36. (http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/377/)

Featured image credit: Aschevogel (Creative Commons BY NC ND)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1nN896f

_________________________________

About the authors

Jonathan Nitzan – York University, Toronto

Jonathan Nitzan – York University, Toronto

Jonathan Nitzan teaches political economy at York University in Canada.

_

_

Shimshon Bichler

Shimshon Bichler

Shimshon Bichler teaches political economy at colleges and universities in Israel. All of his and Jonathan Nitzan’s publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives.

Profit from Crisis: Why capitalists do not want recovery, and what that means for America

On May 27th, Jonathan Nitzan will be speaking at the LSE Department of International Relations public lecture “Can Capitalists Afford Recovery?” More details.

Can it be true that capitalists prefer crisis over growth? On the face of it, the idea sounds silly. According to Economics 101, everyone loves growth, especially capitalists. Profit and growth go hand in hand. When capitalists profit, real investment rises and the economy thrives, and when the economy booms the profits of capitalists soar. Growth is the very lifeline of capitalists.

Or is it?

What motivates capitalists?

The answer depends on what motivates capitalists. Conventional economic theories tell us that capitalists are hedonic creatures. Like all other economic “agents” – from busy managers and hectic workers to active criminals and idle welfare recipients – their ultimate goal is maximum utility. In order for them to achieve this goal, they need to maximize their profit and interest; and this income – like any other income – depends on economic growth. Conclusion: utility-seeking capitalists have every reason to love booms and hate crises.

But, then, are capitalists really motivated by utility? Is it realistic to believe that large American corporations are guided by the hedonic pleasure of their owners – or do we need a different starting point altogether?

So try this: in our day and age, the key goal of leading capitalists and corporations is not absolute utility but relative power. Their real purpose is not to maximize hedonic pleasure, but to “beat the average.” Their ultimate aim is not to consume more goods and services (although that happens too), but to increase their power over others. And the key measure of this power is their distributive share of income and assets.

Note that capitalists have no choice in this matter. “Beating the average” is not a subjective preference but a rigid rule, dictated and enforced by the conflictual nature of the system. Capitalism pits capitalists against other groups in society – as well as against each other. And in this multifaceted struggle for greater power, the yardstick is always relative. Capitalists – and the corporations they operate through – are compelled and conditioned to accumulate differentially; to augment not their personal utility but their relative earnings. Whether they are private owners like Warren Buffet or institutional investors like Bill Gross, they all seek not to perform but to out-perform – and outperformance means re-distribution. Capitalists who beat the average redistribute income and assets in their favor; this redistribution raises their share of the total; and a larger share of the total means greater power stacked against others. In the final analysis, capitalists accumulate not hedonic pleasure but differential power.

Now, if you look at capitalists through the lens of relative power, the notion that they should love growth and yearn for recovery is no longer self-evident. In fact, the very opposite seems to be the case. For any group to increase its relative power in society, that group must be able to strategically sabotage others in that society. This rule derives from the very logic of power relations. It means that capitalists, seeking to augment their income-share-read-power, have to threaten or undermine the rest of society. And one of the key weapons they use in this power struggle –sometimes conscientiously, though usually by default – is unemployment.

Joblessness affects redistribution

Unemployment affects distribution mainly through the impact it has on relative prices and wages. If higher unemployment causes the ratio of price to unit wage cost to decline, capitalists will fall behind in the redistributional struggle, and this retreat is sure to make them eager for recovery. But if the opposite turns out to be the case – that is, if higher unemployment helps raise the price/wage cost ratio – capitalists would have good reason to love crisis and indulge in stagnation.

In principle, both scenarios are possible. But as Figure 1 shows, in America the second prevails: unemployment redistributes income systematically in favor of capitalists. The chart contrasts the share of pretax profit and net interest in domestic income on the one hand with the rate of unemployment on the other (both series are smoothed as 5-year moving averages). Note that the unemployment rate is lagged three years, meaning that every observation shows the situation prevailing three years earlier.

Figure 1 – U.S. Unemployment and the Income Share of Capital

This chart does not sit well with received wisdom. Mainstream economics tells us that the two series should be inversely correlated; that the capitalist income share should rise in the boom when unemployment falls and decline in the bust when unemployment rises. But that is not the case in the United States. In this country, the correlation is positive, not negative. The share of capitalists moves countercyclically: it rises in downturns and falls in booms – exactly the opposite of what economic convention would have us believe. The math is straightforward: for every 1 percent rise in unemployment, capitalists can expect their income share three years later to jump by 0.8 percent. Needless to say, this equation is very bad news for most Americans – precisely because it is such good news for the country’s capitalists.

Remarkably, the positive correlation shown in Figure 1 holds not only over the short-term business cycle, but also in the long term. During the booming 1940s, when unemployment was very low, capitalists appropriated a relatively small share of domestic income. But as the boom fizzled, growth decelerated and stagnation started to creep in, the share of capital began to trend upward. The peak power of capital, measured by its overall income share, was recorded in the early 1990s, when unemployment was at post-war highs. The neoliberal globalization that followed brought lower unemployment and a smaller capital share, but not for long. In the late 2000s, the trend reversed again, with unemployment soaring and the distributive share of capital rising in tandem. Looking forward, capitalists have reason to remain crisis-happy: with the rate of unemployment again approaching post-war highs, their income share has more room to rise in the years ahead.

The power of capitalists can also be examined from the viewpoint of the infamous Top 1 percent. Most commentators stress the “social” and “political” problems created by the disproportional wealth of this group, but this emphasis puts the world on its head. Redistribution is not an unfortunate side-effect of growth and stagnation, but the main force driving them.

Figure 2 shows the century-long relationship between the income share of the Top 1 percent and the annual growth rate of U.S. employment (with both series smoothed as 10-year moving averages). And as the chart makes clear, the distributional gains of this group have been boosted not by growth, but by stagnation. The overall relationship is clearly negative. When stagnation sets in and employment growth decelerates, the income share of the Top 1 percent actually rises – and vice versa during a long-term boom.

Figure 2 – U.S. Income Distribution and Employment Growth

Historically, this negative relationship can be divided into three distinct periods, indicated by the dashed, freely drawn line going through the employment growth series. The first period, from the turn of the twentieth century till the 1930s, is the so-called Gilded Age. Income inequality is rising and employment growth is plummeting.

The second period, from the Great Depression till the early 1980s, is marked by the Keynesian welfare-warfare state. Higher taxation and public spending make distribution more equal, while employment growth accelerates. Note the massive acceleration of employment growth during the Second World War and its subsequent deceleration brought by post-war demobilization. Obviously these dramatic movements were unrelated to income inequality, but they did not alter the series’ overall upward trend.

The third period, from the early 1980s to the present, is marked by neoliberalism. In this period, monetarism assumes the commanding heights, inequality soars and employment growth plummets. The current rate of employment growth hovers around zero while the Top 1 percent appropriates 20 per cent of all income – similar to the numbers recorded during Great Depression.

So what do these facts mean for America?

First, they make the fault-lines obvious. The old slogan “what’s good for GM is good for America” now rings hollow. Capitalists seek not utility through consumption but more power through redistribution. And they achieve their goal not by raising investment and fueling growth, but by allowing unemployment to rise and jobs to become scarce. Clearly, we are not “all in the same boat.” There is a distributional struggle for power, and this struggle is not a mere “sociological” issue. It is the center of our political economy, and we need a new theoretical framework to understand it.

Second, macroeconomic policy, whether old or new, cannot offset the aggregate consequences of this distributional struggle. Not by a long shot. Till the late 1970s, the budget deficit was small, yet America boomed. And why? Because progressive taxation, transfer payments and social programs made the distribution of income less unequal. By the early 1980s, this relationship inverted. Although the budget deficit ballooned and interest rates fell, economic growth decelerated. New methods of upward redistribution have caused the share of the Top 1 percent to zoom, making stagnation the new norm.

Third, and finally, Washington can no longer hide behind the bush. On the one hand, the concentration of America’s income and assets, having been boosted by large post-crisis bailouts and massive quantitative easing, is now at record levels. On the other hand, long-term unemployment remains at post-war highs while job growth is at a standstill. Eventually, this situation will be reversed. The only question is whether it will be reversed through a new policy trajectory or through the calamity of systemic crisis.

On May 27th, Jonathan Nitzan will be speaking at the LSE Department of International Relations public lecture “Can Capitalists Afford Recovery?” More details.

This article was originally published in Frontline on 16 April, and is based on the paper: Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, ‘Can Capitalists Afford Recovery? Economic Policy When Capital is Power’, Working Papers on Capital as Power, No. 2013/01, October 2013, pp. 1‑36. (http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/377/)

Featured image credit: Aschevogel (Creative Commons BY NC ND)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1nN896f

_________________________________

About the authors

Jonathan Nitzan teaches political economy at York University in Canada.

_

_

Shimshon Bichler teaches political economy at colleges and universities in Israel. All of his and Jonathan Nitzan’s publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

Reddit

Tumblr

Google +1

Pinterest

Email

Related Posts

Mass migration has left a positive legacy on economic development in the U.S.

There is no need for the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership agreement to include investor-state arbitration

Public funding of elections increases candidate polarization by reducing the influence of moderate donors.

Less comprehensive social policies may contribute to lower life expectancies and worse health in the U.S. compared to other high-income countries.

Under Democratic presidents, minorities make economic gains – and so do whites

Why everyone does better when employees have a say in the workplace

The current recession may be forming a generation that wants more state intervention, redistribution, and will accept higher taxes.

A ‘Precariat Charter’ is required to combat the inequalities and insecurities produced by global capitalism

African-Americans support the Democratic Party because they perceive it to be more competent than the GOP on important issues.

Spending rises are more effective in expanding the economy by as much as 20 percent compared to tax cuts

Felon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacy

Book Review: Our America: A Hispanic History of the United States by Felipe Fernández-Armesto

Book Review: Decentralization and Popular Democracy: Governance from Below in Bolivia by Jean-Paul Faguet

The rise of the robots means we need progressive politics more than ever

Leaders must focus on fixing the inequality of labor income in the U.S.

Book Review: Media and the Rhetoric of Body Perfection: Cosmetic Surgery, Weight Loss and Beauty in Popular Culture by Deborah Harris-Moore

Book Review: Making Democracy Fun: How Game Design Can Empower Citizens and Transform Politics by Josh Lerner

Patriarchy continues to loom large over representations of Black masculinity in the age of President Obama

Book Review: Mass Flourishing: How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge and Change by Edmund Phelps

Book Review: The Impact of Racism on African American Families: Literature as Social Science by Paul C. Rosenblatt

A global progressive tax on individual net worth would offer the best solution to the world’s spiralling levels of inequality

Mormons remain outsiders in American Politics

Business-targeted tax cuts do not improve state economies

However you spend it, money isn’t the key to happiness

Professional campaigners are socially removed from low-income communities and taught to ignore them at election time, perpetuating political inequalities

Congressional gridlock helps to make income inequality worse

People across the world are protesting their lack of real democracy

Rising wealth concentration helped lead to the 2008 financial crisis and continues to contribute to ongoing financial instability

Despite the likely declassification of the Senate report on CIA’s practices, the U.S. government still maintains vast capabilities to spy on its own citizens.

Protests focused on drones distract from the real issue of using targeted killings as a counter-terrorism strategy

Book Review: Wrong: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them by Richard S. Grossman

Fracking is unlikely to reduce gas prices to the extent its proponents desire

Michael Sam’s coming out is a challenge to the vicarious masculinity that American men derive from the NFL

Plural relationships, when consensual and gender-neutral, may actually help reduce gender inequality.

Five minutes with Ulrich Beck: “Digital freedom risk is one of the most important risks we face in modern society”

Despite assertions to the contrary, the New Deal’s fiscal policies were key to ending the Great Depression.

The collapse in bank lending in 2008-09 led directly to falling employment at nonfinancial firms.

Book Review: Deliberating American Monetary Policy: A Textual Analysis by Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey

When art coaxed the soul of America back to life

Book Review Forum: Dynamics among Nations: The Evolution of Legitimacy and Development in Modern States by Hilton Root

Anti-Hispanic prejudice drives opposition to immigration in the U.S.

Workplace technology use may increase both employees’ distress and productivity

Book Review: After Civil Rights: Racial Realism in the New American Workplace by John D. Skrentny

Book Review: Civic Participation in America by Quentin Kidd

International organizations must take the lead on reducing income inequality

Virtual hybrid communities show that you don’t have to meet face-to-face to advance great ideas

When evaluating the benefits of trade policy, policymakers need to take into account the potentially negative effects on workers’ incomes.

Voters only punish female candidates who use negativity in their campaigns if they are from the opposing party

Book Review: Propaganda, Power and Persuasion: From World War One to Wikileaks by David Welch

Book Review: Save Our Unions: Dispatches from a Movement in Distress by Steve Early

Policymakers follow pertinent academic research, but see much of it as irrelevant to their work

People’s subjective expectations about their own future health can teach us a great deal about their attitudes towards smoking.

The revolution will not be bought: Ethical consumption is seductive but dangerous to the values ethical consumers seek to promote

Stable sectors may benefit from recessions by recruiting more talented workers

Book Review: The Ecological Hoofprint: The Global Burden of Industrial Livestock by Tony Weiss

Book Review: Anime: A History by Jonathan Clements

Rising inequality and the need for a divorce between democracy and capitalist interests

Public support for female politicians is contingent on economic and political contexts

Women are more responsive to female senators’ records, which may increase accountability

The social cure: Why groups make us healthier and how policymakers can capitalise on these curing properties

The massive inflow of foreign capital in the 2000s that enabled the American credit bubble was primarily from the private sector, not governments.

Public debt, GDP growth, and austerity: why Reinhart and Rogoff are wrong

Book Review: The Scramble for the Amazon and the Lost Paradise of Euclides da Cunha by Susanna B Hecht

Few have ever doubted the quality of Robert Dahl’s work

Evidence from Chicago shows that declining job accessibility for the poor is a result of socioeconomic, but not spatial, factors.

Airports have a small benefit on employment in local service sectors, but no measurable effect on others.

Lamenting the decline of the manufacturing sector misses the fact that the service sector is increasingly important for future growth

Legislative efforts to rein in executive pay have been largely symbolic

The implementation of the Affordable Care Act has undermined public trust in government

Book Review: How Numbers Rule the World: The Use and Abuse of Statistics in Global Politics by Lorenzo Fioramonti

Book Review: Does Capitalism Have A Future? by Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian and Craig Calhoun

Contrary to popular belief, Adam Smith did not accept inequality as a necessary trade-off for a more prosperous economy

Rio de Janiero is coming to terms with the brutality of urban transformation that can come with mega-events like the Olympics.

In the long run, the Supreme Court leads public opinion on controversial issues

An increase in the federal minimum wage is now likely

Increasing the minimum wage does not necessarily reduce employment

Book Review: Memes in Digital Culture by Limor Shifman

Lower levels of inequality are linked with greater innovation in economies

The vast majority of U.S. federal debt is now held by the richest households and largest companies, raising concerns about inequality and power.

Book Review: The Political Web: Media Participation and Alternative Democracy

The Fed’s tapering gives us the chance to focus on the economy’s real problems

Book Review: The Impact of Research in Education: An International Perspective

The impact of immigration and offshoring on American jobs is far more complicated than directly replacing workers

Book Review: Citizens Rising: Independent Journalism and the Spread of Democracy

Book Review: Banking on Democracy: Financial Markets and Elections in Emerging Countries

Book Review: Global Rivalries: Standards Wars and the Transnational Cotton Trade

Book Review: Perspectives on Strategy

Congress has a very limited ability to hold central bankers to account.

Media portrayals of military women reflect recruitment conditions, but political power relations and foreign policy contexts matter as well

Book Review: Mexico’s Struggle for Public Security: Organized Crime and State Responses

Lockup quotas in U.S. prisons are not necessarily a tax on low crime, and may actually help maximise value for money for taxpayers.

Book Review: Women and Journalism

Ayn Rand rewrote the story of capitalism to show that it is a necessary good

U.S monetary policy is less powerful in recessions

The U.S. shutdown has a hefty international price tag

In its opposition to the Affordable Care Act, the Tea Party is not defending the ideals of the founding fathers, but subverting them.

Union members are more likely to give to charity, and to give more when they do.

Senators of both parties respond to the preferences of the wealthy, and ignore those of the poorest.

Book Review: Black Citymakers: How ‘The Philadelphia Negro’ Changed Urban America

Beliefs in conspiracies tend to accord with political attitudes, making it unlikely that any one conspiracy theory will be embraced by the country.

In desirable cities, property owners and developers influence tighter land use regulations, which can lead to substantially higher urban and housing costs.

Americans may view government negatively, but in film they see positive depictions of individual civil servants.

This fall, disputes over the debt ceiling, sequestration cuts, the budget, and Syria may lead to an imperfect political storm in Washington.

Recent weeks have sharply exposed the lack of direction in Washington’s policy on Syria.

After significant reforms, Canada’s political parties now have their income and expenditure closely controlled, and are more dependent on public funds.

Policies aimed at increasing electoral competition and campaign spending would help address low levels of voter turnout in city elections.

After many years of electoral disappointment, the Democrats are now the front runners in the New York mayoral race.

Including Canada and Mexico in an EU-US free trade agreement would create a genuine transatlantic market that would deliver significant economic benefits.

Presidential campaigns are less important than previously thought in influencing how people vote

The politics of punishment in America are slowly moving away from the mass incarceration policies of the past.

The Fed’s monetary policies since 2008 have undermined the creation of a growth-producing economic environment.

Unlike Detroit, Chicago’s diversified industrial base has helped it to successfully switch from a material to a knowledge economy.

Book Review: European and American Extreme Right Groups and the Internet

Book Review: Border Rhetorics: Citizenship and Identity on the US-Mexico Frontier

Book Review: Martin’s Dream: My Journey and the Legacy of Martin Luther King Jr

Book Review: American Neoconservatism: The Politics and Culture of a Reactionary Idealism