Working Papers on Capital as Power, No. 2018/01, April 2018

[Illustration by Elvire Thouvenot-Nitzan elvirethouvenot.com]

With their Back to the Future:

Will Past Earnings Trigger the Next Crisis?

Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan [1]

Jerusalem and Montreal, April 2018

![]() bnarchives.net / Creative

Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

bnarchives.net / Creative

Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

1. Why is the Stock Market Tanking?

The U.S. stock market is again in turmoil. After a two-year bull run in which share prices soared by nearly 50 per cent, the market is suddenly dropping. Since the beginning of 2018, it lost nearly 10 per cent of its value, threatening investors with an official ‘correction’ or worse.

As always, there is no shortage of explanations. Politically inclined analysts emphasize Trump’s recently announced trade wars, sprawling scandals and threatening investigations, as well as the broader turn toward ‘populism’; interest-rate forecasters point to central-bank tightening and china’s negative credit impulse; quants speak of breached support lines and death crosses; bottom-up analysts highlight the negative implications of the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica debacle for the ‘free-data’ business model; and top-down fundamentalists indicate that, at near-record valuations, the stock market is a giant bubble ready to be punctured.

And on the face of it, these explanations all ring true. They articulate various threats to future profits, interest rates and risk perceptions, and since equity prices discount expected risk-adjusted future earnings, these threats imply lower prices.

But there is one little problem. Unlike their pundits, capitalists nowadays tend to look not forward, but backward: instead of matching asset prices to the distant future, they fit them to the immediate past.

2. With their Back to the Future

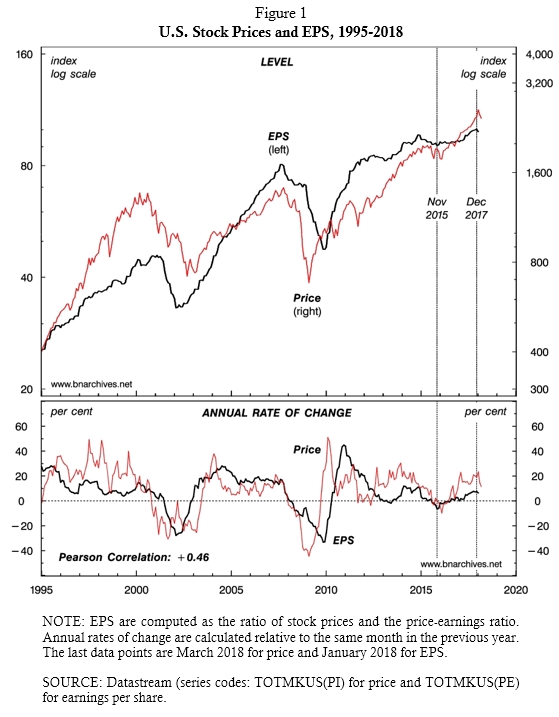

Judging by Figure 1, the main driver of U.S. stock prices is current earnings per share, or EPS. [2] The chart contrasts monthly data for EPS and share prices since 1995. The top panel plots the levels of the two variables, while the bottom panel shows their annual rates of change, and in both cases the temporal pattern leaves little doubt: share prices and current earnings are tightly correlated.

Before we proceed, it is worth noting that ‘current’ earnings are not exactly current: the EPS for a given month are earned not during that month but up two years earlier. The reason is twofold. First, each EPS observation is a 12-month trailing average of previously reported earnings. And second, each of these previously reported earnings represents profits earned in the previous year. All in all, then, each EPS observation covers 12 to 24 months’ worth of profits, so if stock prices are indeed driven by EPS, they are driven not by current profits, but by past ones.

These considerations have two implications. The first and less important is that, contrary to popular belief, the recent market trajectory – i.e., its increase till December 2017 and its drop since February 2018 – has had little to do with President Trump. As the chart shows, when Trump took office in January 2017, prices were already rising on the back of an EPS recovery that started in November 2015 (marked by the first vertical dotted line). EPS growth accelerated after Trump entered the White House, but since EPS data represent profits earned up to two years earlier, this acceleration could not have been influenced by Trump’s election, let alone his policies. Similarly with the 2018 price drop: as the figure shows, the February market decline came after EPS fell in January 2018 (second vertical dotted line), and since most of the profits represented by January’s EPS were earned before Trump’s policies came into effect, they could not have been significantly influenced by those policies to start with.

The second implication is broader and much more important. According to the data, present-day capitalists seem to view the world much like the Aymara people of Southern Peru and Northern Chile do: with their back to the future. The Aymara language reverses the directional-temporal order of most other languages: it treats the known past as being ‘in front of us’ and the unknown future as lying ‘behind us’. [3] And judging by the Pearson correlation coefficient recorded in the bottom panel, capitalists do the same: since 1995, a full 46 per cent of the (squared) variations in the rate of change of stock prices can be explained by variations in the rate of change of past earnings.

This Aymara-like behaviour borders on sacrilege. According to finance textbooks, investors should look not backward, but forward. Their standard capitalization ritual, reiterated endlessly by the scientists of finance, conditions and compels them to discount not past profits, but future ones. Moreover, since corporations – and the capitalist system more generally – have no ‘expiry date’, their owners should look far beyond their immediate horizons. To properly price their assets, they must discount the profits they expect to earn not in the next few quarters or even several years, but all the way to ‘eternity’ (Benjamin Graham, quoted in Zweig 2009: 28).

But if so, why do present-day capitalists defy their most sacred ritual and, instead of peering into deep future, remain fixated on the immediate past?

3. The Radical Inversion

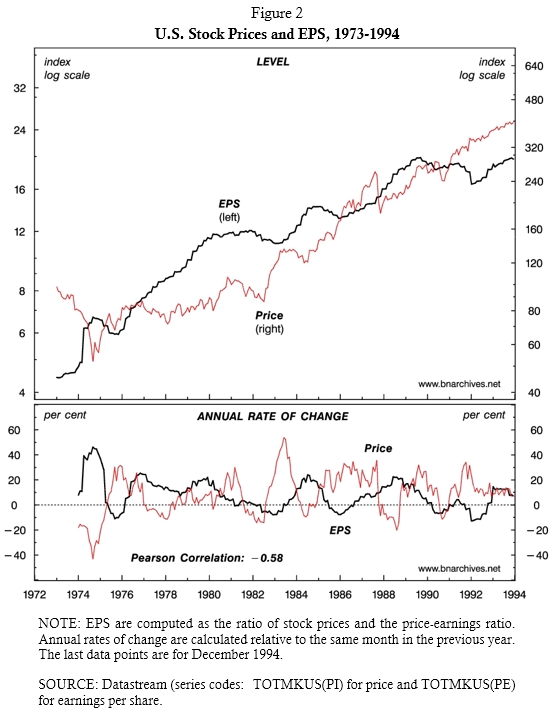

To complicate things further, according to Figure 2 this backward-looking posture is in fact rather new. As the bottom panel shows, until 1995 the cyclical growth rates of stock prices and EPS moved not together, but inversely: whereas the Pearson correlation between these rates was +0.46 in the post-1995 period, in the pre-1995 era it was –0.58. In other words, whatever affected the growth rate of stock prices from 1973 to 1995, it was not the growth rate of recent profits.

This radical inversion is highly perplexing. Why would capitalists obey their rituals in one period only to ignore it in the next? What happened in the mid-1990s that made them shift from forward- to backward-looking asset pricing? What does this shift mean for the broader logic of capital accumulation? And what does it imply for the near future?

4. Systemic Fear: The Power of Denial

In our paper ‘A CasP Model of the Stock Market’ (Bichler and Nitzan 2016), we argued that the extent to which capitalists look backward rather than forward is indicative of their ‘systemic fear’ – namely, their apprehension for the very future of capitalism. [4]

Since capitalization is forward-looking, variations in current profits should have no more than a negligible impact on asset prices, and variations in past profits should have no impact at all. Exclusive reliance on the future attests the capitalists’ systemic confidence. It demonstrates their belief that earnings will continue to flow and that assets will always have buyers – in other words, that their current system is eternal, and that the ritual of capitalization will dominate the world forever.

Now imagine the opposite situation – a setting in which capitalists lose this systemic confidence in the future and are instead struck by systemic fear, the apprehension that the current mode of power might crumble. Interestingly, the capitalists’ immediate reaction to systemic fear is not capitulation, but denial: ‘What? We worry? Fear for our system? No way!’ To sustain this denial and retain a semblance of confidence, though, capitalists need proof; they need evidence that they are still in driver’s seat, and the most readily available evidence of such control is their EPS here and now (read in the most recent past). If EPS remain high – or better still, if they continue to rise – then we, the capitalists, can remain hopeful despite the threatening future. And if our group as a whole stays hopeful, then, as individual investors, we have good reason to hold on to and even augment our equity holdings.

Paradoxically, then, the evidence for systemic fear lies in its very denial. We can know that capitalists have been struck by systemic fear by the fact that they effectively negate and abandon their core ritual of forward-looking capitalization; and we can measure the degree to which they negate this ritual by the extent to which their asset pricing comes to depend on past or current earnings rather than future earnings. This power of denial underpins our systemic fear index.

5. The Systemic Fear Index

The systemic fear index measures the short-term correlation between stock prices and EPS. The higher this correlation, we argue, the greater the reliance of equity pricing on current and past earnings and, by implication, the more fearful capitalists are for their system’s future.

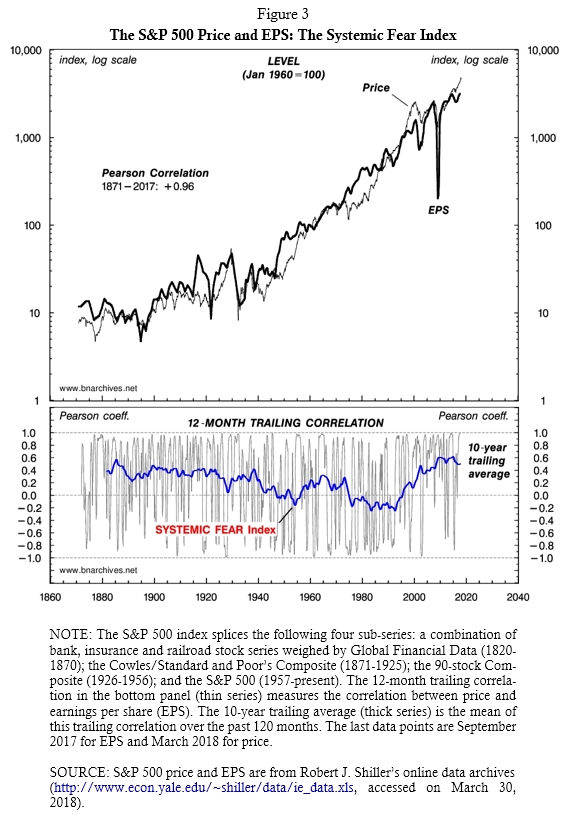

Figure 3 shows the construction of this index. [5] The top panel shows monthly price and EPS data for the S&P 500 group of companies, dating back to 1871. The bottom panel plots short-term correlations. The thin series in the bottom panel measures the 12-month trailing correlation between the price and EPS series shown in the top panel. Each observation shows the correlation over the past year, with a value ranging between –1 (perfect inverse correlation) and +1 (perfect direct co-movement). [6]

The difficulty with the thin 12-month trailing correlation is that it oscillates widely, so visual inspection alone is not very revealing here. The thick series in the bottom panel addresses this difficulty by smoothing the thin series as a ten-year trailing average. Each observation in the thick series measures the average 12-month trailing correlation between price and EPS over the previous ten years. [7] We call this series the systemic fear index.

6. The Evolution of Systemic Fear

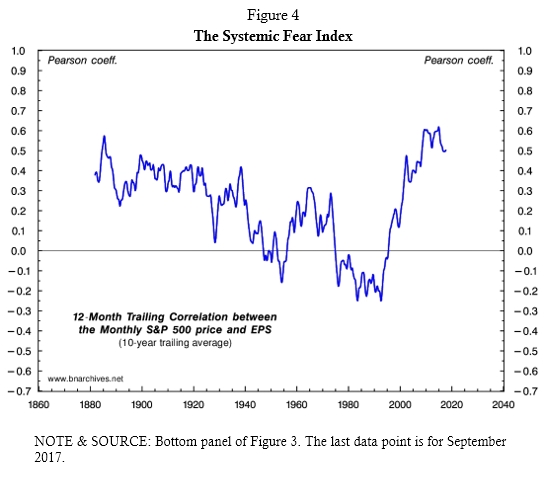

Figure 4 enlarges our systemic fear index taken from the bottom panel of Figure 3, making it easier to examine. The chart shows two clear patterns: one long term, the other shorter term. The long-term pattern has a V‑shape, with the early 1990s as its low point. Until the early 1920s, forward-looking capitalization was still in its infancy, so the correlation between price and EPS was pretty high, hovering around +0.4. [8] But even then, there was already a visible down drift, and by the 1940s this down drift had turned into a sharp decline. Discounting methods were now making their way into introductory textbooks, and by the 1950s, with the capitalization ritual becoming more widely accepted and increasingly internalized by equity investors, the correlation fell to around zero. For the next half century, the index hovered around this value – albeit with some significant oscillations (the lack of correlation during this period is evident in the bottom panel of Figure 2).

And then came a decisive upward reversal. It started in the mid-1990s, and initially the uptick looked like part of yet another short oscillation. But by the early 2000s it became evident (at least in retrospect) that the century-long downtrend had been broken. Instead of reverting back to zero, the systemic fear index continued to soar and, by the early 2010s, reached an all-time high of +0.6 (the tightening correlation during this period is evident in Figure 1).

This V-shape pattern, though, has been anything but smooth. Oscillating around the long-term down- and uptrends are plenty of shorter-term fluctuations, some of which are pretty pronounced. So the question we need to address is what lies behind these patterns: what determines the long-term V-shape of the index and what accounts for its shorter-term fluctuations?

7. Short-termism: Culture or Power?

At stake here is the connection between the two key quantities of the capitalist nomos – the price of capital and its underlying earnings – so the question is obviously important. [9] Yet, to the best of our knowledge, that question has never been asked, let alone answered. Indeed, as far as we know, the V‑shape pattern of the short-term price-EPS correlation shown in Figures 3 and 4 is a new finding.

It is common to argue that, since the 1980s, U.S. capitalism has been marked by a growing emphasis on ‘shareholder value’, heightened ‘short-termism’ and a nearly universal obsession with quarterly increases in profits. This popular view is certainly consistent with the post-1980s surge of the price-EPS correlation shown in Figure 4 – and this consistency should hardly surprise us. With capitalists paying more and more attention to the latest bottom line and analysts glued to the latest bit of news, it is no wonder that equity markets have become increasingly sensitive to the most recent variations in earnings. [10]

But what is the cause of these changes? Why has the capitalist time horizon shrunk? Why have investors – who, for a whole century up until that point, cared less and less about current earnings and often seemed perfectly happy to buy and hold stocks for the long haul – suddenly started to insist on quarterly increases in profits? Is the V‑shape reversal of the early 1990s merely the consequence of a changing ‘investment culture’? Is it simply a new fad imprinted by the theoretical winds of just-in-time neoliberalism and emboldened by the ideological flare of Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan and Alan Greenspan – or are these developments themselves the result of a deeper change?

The evidence presented below suggests the latter. Present-day capitalists and analysts, we argue, have come to demand quarterly increases in profits not because they started to ‘feel like it’, because they were taken over by a new financial ‘fashion’ or because they were somehow convinced that short-term increases are more ‘economically efficient’ than long-term growth. In our view, they do so because they are compelled to, and the force that compels them has nothing to do with any of the above. The reason, rather, is that their capitalized power is approaching its asymptotes, and the only way for them to counteract their deepening systemic fear is by pushing for higher current earnings. [11]

8. Capitalized Power and Systemic Fear

In ‘A CasP Model of the Stock Market’ (Bichler and Nitzan 2016), we developed a capitalized power index, defined as the ratio of the S&P 500 price index and the average wage rate. The numerator and denominator of our power index represent a conflict: the clash between those who own the capitalized means of power and those who are controlled by them.

Note that we use the average wage rate here not as a measure of productivity or wellbeing, but as a benchmark against which to gauge the differential power of owners. Furthermore, although strictly speaking the wage rate pertains only to employed workers, its temporal movement approximates, however crudely, the changing conditions of the underlying population at large. Thus, when our power index rises, this means that the power of equity owners relative to the underlying population increases – and vice versa when the index falls. Moreover, and importantly, this relative power is forward looking: it denotes not only the rulers’ relative position here and now, but also how they expect this relative position to change in the future.

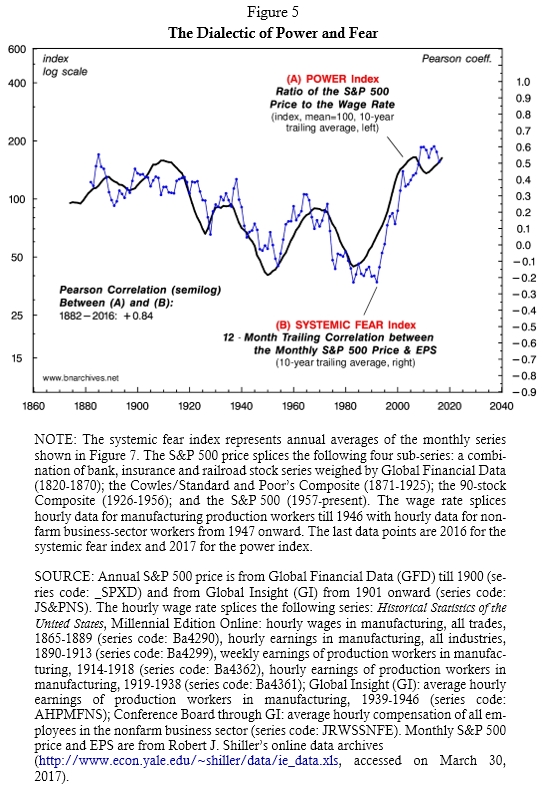

Now, as Figure 5 indicates – and here we come to the crucial point – our power and systemic fear indices seem to move in tandem. The dotted blue series, plotted against the right scale, is our systemic fear index, taken from Figure 4 (to reiterate, this index is the ten-year trailing average of the 12-month trailing correlation between the S&P 500 price and EPS). The solid black series, plotted against the left log scale, is our power index, smoothed as a ten-year trailing average to match the periodicity of the systemic fear index. And as the data show, the correlation between them is very tight: its Pearson coefficient for the past 134 years is +0.84 out of a maximum of +1.

What this correlation tells us is that the greater the capitalized power of equity owners relative to the underlying population, the greater their systemic fear and therefore the greater their reliance on current earnings when pricing their stocks – and conversely, the lesser their capitalized power, the lower their systemic fear and hence the weaker their emphasis on present profits.

9. The Dialectic of Power and Fear

At first sight, this co-movement might seem counterintuitive. Why should capitalists fear more for their system as they grow more powerful? Shouldn’t it be the other way around – i.e., the greater their power, the lesser their systemic fear?

To answer this question, we need to backtrack a bit. Power is a complex and often slippery concept. It has numerous dimensions and layers, it is historically contingent and context-dependent and, most importantly, it is deeply dialectical and self-transformative. In our own research, we extend Johannes Kepler’s scientific notion of force to view capitalized power not as a stand-alone qualitative entity, but as a quantitative relationship between entities (Nitzan and Bichler 2014: 141). Here, we define this power very broadly as the relationship between equity owners and the underlying population, quantified by the ratio of stock prices to the wage rate. But we also argue that the quantity of capitalized power expresses the rulers’ confidence in the obedience of the ruled (Nitzan and Bichler 2009: 17) – which in our case here denotes the confidence of equity owners in the obedience of the underlying population.

Confidence in obedience, though, is not a monolithic sentiment. If we are to generalize, we might say that the buildup of power generates not one, but two movements – one extroverted, the other introverted – and that the trajectories of these two movements are not similar but opposite. On the outside, the relationship appears positive: the greater the rulers’ power, the greater their display of confidence in obedience. But on the inside, the connection is negative: the more powerful the rulers, the greater their fear that their power might crumble.

This double-sided relationship is the linchpin of Hobbes’ Leviathan (1691). The relatively equal abilities of human beings, he says, breed their uncertainty, insecurity and mutual suspicion, and these forces in turn compel them to try to increase their differential power without end. But, then – and this is the crucial qualifier – the more power one possesses, the more he or she dreads losing it all. The result is an ongoing cycle, with fear stoking a hunger for power, and the amassment of power heightening the very fear that begot that hunger in the first place (for example, pp. 75 and 94).

Now consider how this double movement unfolds in our case here. Capitalists, we posit, are driven to increase their capitalized power without end, and this increase, we maintain, boosts their expressed confidence in obedience. And how do we know that their confidence in obedience is indeed rising? Because the stock prices comprising the numerator of the power index are determined by the capitalists themselves, and because capitalists determine those prices by risking the thing they cherish the most: their own money. Indeed, the only reason for capitalists to buy stocks and in so doing bid up the stock price/wage ratio is that they expect this ratio to rise even further. And the fact that they believe that this ratio will go up attests to their confidence in obedience – the confidence that the underlying population will not expropriate them and that the system as a whole will not fail them. In this sense, our power index offers an objective measure of capitalist confidence – at least on the outside.

But as Figure 5 shows, there is another, inner process at work here: the temporal basis for capitalist confidence in obedience varies with the level of capitalized power. When the power index is low, the projected confidence of capitalists is inherently forward-looking. During such periods – for example, the 1940s or the 1980s – capitalists focus on the future and ignore present profits altogether (as indicated by the low, zero or even negative price-EPS correlation). And why? Because the lower the capitalized power, the greater the scope for increasing it further.

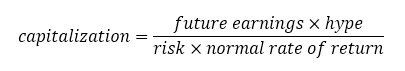

In our earlier work (Bichler and Nitzan 2006; Nitzan and Bichler 2009: Ch. 11), we developed the notion of the ‘elementary particles’ of capitalization – future earnings and investors’ hype in the numerator of the capitalization formula, and risk and the normal rate of return in the denominator:

When the power index is low – as it was, for instance, during the 1940s and 1950s and, again, during 1980s – the elementary particles of capitalization can be augmented/reduced to boost it further: income can be further redistributed in favour of profits; investors’ hype can be further amplified; profit volatility and therefore risk perceptions can be further decreased; and the normal rate of return can be further lowered. And as long as the potential for further augmentation/reduction in favour of capital remains large, equity owners can safely ignore the dismal present and capitalize the promising future. [12]

However, when the power index is high – as it was, for example, during the early twentieth century, and as it is now, at the beginning of the twenty-first – confidence in obedience must rely largely on the present (and it does, as shown by the high price-EPS correlation during these periods). And why? Because capitalized power is not unbounded. The greater the power, the greater the resistance to power. And when power approaches its asymptotes – in this case, when the profit share of income and the level of hype are already high and income volatility and the normal rate of return already low – increasing it further within the existing confines of the ‘symbolic machine’, as Ulf Martin (2010) calls it, becomes harder and harder (Bichler and Nitzan 2012). Such increases require further threat, sabotage and open force, which in turn make the system ever more complex and increasingly brittle, and hence prone to breakdown (Bichler and Nitzan 2010). Under these circumstances, the only way for capitalists to retain their apparent confidence is to be constantly reassured that the system still holds here and now. And since the future is too bleak to rely on, this reassurance can come only from current profits

10. The Omen

Rulers always need an omen, a self-serving looking glass to bolster their confidence and galvanize their resolve. But sometimes the omen refuses to cooperate, and when it disobeys, the façade crumbles and the rulers find themselves facing the void. Literature offers many illustrious examples: the evil queen in the Brothers Grimm’s Little Snow-White, whose obedient magic mirror suddenly defies her, declaring that she is not the fairest of all; Genghis Khan in Aitmatov’s The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years (1983), whose loyal guiding cloud suddenly disappears, leaving the Khan’s globetrotting conquest in tatters; Belshazzar, the omnipotent king of Babylon, whose hubris is suddenly deflated by a mysterious writing on the wall (Book of Daniel: Ch. 5); the list goes on.

These power mirrors, though, are pretty naïve. They typically generate no more than a binary image, and their warnings almost always come too late. By contrast, the stock price-EPS correlation offers an infinitely nuanced reflection. Instead of a binary image, it draws a continuous scale, ranging from a Pearson coefficient of 0 (or less), which indicates that forward-looking capitalists do not fear for their system, to a Pearson coefficient of +1, which means that capitalists, struck by systemic fear, have completely abandoned their core belief in forward-looking capitalization in favour of a defensive, backward-looking posture.

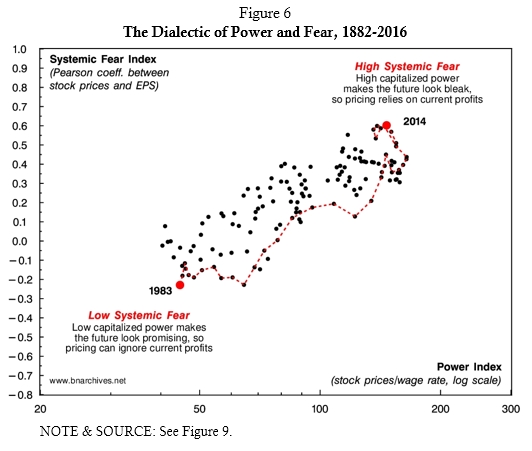

This analytical range is shown historically in Figure 6. The chart presents the same data series from Figure 5, but instead of displaying them on a time scale, it plots them against one another. Each annual observation projects two readings: the ten-year trailing average of the power index on the horizontal scale, and the systemic fear index on the vertical scale. The observations are tightly clustered around a positive slope, reconfirming what we have already seen in Figure 5 – namely, that capitalized power is closely intertwined with systemic fear. For illustration purposes, we use a dashed red line to trace the evolution of this temporal relationship during the most recent period: from 1983, when the systemic fear index was at a record low, to 2014, when it reached its all-time high.

The gradual temporal ‘stretching’ of this dashed line has been akin to pulling a string: as the United States moved up and to the right on this path, the tension between sabotage and resistance kept rising and rising. However, because the process has been so slow and drawn out, initially this buildup was largely imperceptible. Indeed, until recently the key ‘actors’ themselves – i.e., the capitalists and fund managers, along with policymakers and opinion shapers – remained largely unware of it and seldom admitted it, not even to themselves (and rarely if ever in the manner described here). But as Thorstein Veblen might have put it, although they are yet to recognize it with their mind, they already know it in their heart. And here their actions speak louder than words: with their power rising, they have gradually but systematically abandoned their sacred ritual of forward-looking capitalization in favour of the still-rosy present. Their current mode of power is becoming increasingly unstable, and their short-term equity pricing indicates that underneath the hubris lies a deepening apprehension that it might not last.

Our own study of redistribution as the key power axis of capitalism started during the early 1980s. At the time, U.S. capitalized power and systemic fear were at all-time lows, investors were totally oblivious to the issue and our work was typically classified as ‘social economics’ (with an aftertaste of moralizing ‘social justice’). But as capitalized power and systemic fear increased, the crucial importance of redistribution slowly percolated to the surface, and in 2014, when power and fear reached record highs, Thomas Piketty’s work on inequality (Piketty 2014) was suddenly made top news and everyone suddenly knew (all along) that the top 1 per cent held the rest of the world under its thumb.

And then the discourse started to change. Although the talking heads still hail capitalism as the best of all possible worlds, by the mid-2010s we started to see more and more expressions of guilt (the IMF admitting that the project of neoliberal globalization has been 'oversold'; Ostry, Loungani, and Furceri 2016), remorse (McKinsey cautioning that the current generation is poorer than its parents; McKinsey & Company et al. 2016), doubts about the ability of ‘economics’ to remain sheltered from ‘politics’ (hedge-fund billionare Ray Dalio predicting that from now on 'populism' will shape economic conditions more than 'classic monetary and fiscal policies'; Dalio et al. 2017) and dire warnings about the very future of the capitalism (former bond king Bill Gross alerting his fellow capitalists that, although ‘I’m an investor that ultimately does believe in the system’, I believe that ‘the system itself is at risk’; Gittelsohn 2016). With U.S. redistributional tensions remaining at an all-time high, many savvy investors sense that sooner or later the spring will snap, and as confidence crumbles and the rulers run for the stock-market doors, a new major bear market (MBM) will get under way. [13]

11. The Cunning of History: Will Past Earnings Trigger the Next Crisis?

If current market jitters develop into an MBM, the consequences are likely to be dramatic. Over the past two centuries, the United States has experienced seven MBMs with an average market drop of 57 per cent in constant dollars (Bichler and Nitzan 2016: Table 1, p. 122). Current U.S. market capitalization is almost $30 trillion, so a ‘typical’ MBM could end up wiping out $17-trillion worth of capitalist assets. And that is just for starters.

During the past century, every MBM has been followed by a major creordering of capitalized power and a significant rewriting of the capitalist nomos. [14] Thus, the MBM of 1905-1920 was followed by the rise of corporate capitalism; the MBM of 1928-1948 was followed by the rise of the Keynesian welfare-warfare state; and the MBM of 1968-1981 was followed by the rise of global neoliberalism. The consequences of first MBM of the twenty-first century, from 1999 to 2008, are still hard to pin down, but one them seems to be a gradual shift toward a harsher mode of power – perhaps along the lines of Jack London’s The Iron Heel (1907). For this authoritarian shift to gain traction, though, capitalism might have to experience another MBM, hence the crucial important of the current moment.

If our analysis here is correct, it follows that the very future of capitalism is now at stake. Yet, paradoxically, the recent history of the stock market cunningly suggests that this future now hinges on the trajectory of . . . past profits.

As Figure 1 shows, the two down legs of the most recent MBM – in 2000-2003 and then in 2007-2008 – were both triggered by and/or coincided with a significant decline in earnings. Now, since both downturns began when the power and systemic fear indices were extremely high (Figure 5), this co-movement is exactly what our model predicts. And ominously, the present situation is practically the same: just like in the runup to the two previous downturns, the power and systemic fear indices are extremely high; and as before, these high levels mean that investors, standing with their back to the future, remain extremely sensitive to the direction of current earnings.

So which way will earnings go?

In our opinion, the more likely direction is down, and, prosaically, the main reason is timing. For corporate earnings to continue to rise, there must be further upward income redistribution – from the underlying population to capitalists. Now, as noted, given that the U.S. capitalist share of income and personal income inequality are already at record levels, this redistribution is likely to require a much more authoritarian mode of power; and as the 2017 U.S. election of Donald Trump and the so-called ‘populist turn’ around the world suggest, the push in that direction might already be underway. However, even if a harsher mode of power were to emerge – and at this point, it is hard to say whether it will – this emergence will take time and its impact on EPS will register only with a considerable lag.

And it is here that timing becomes critical. Standing with their back to the future and their eyes staring at the most recent past, U.S. capitalists remain extremely sensitive to even a small drop in earnings, and the cyclical backdrop they are currently looking at is highly unfavourable. The present U.S. expansion is already the second longest in history, interest rates are already at historic lows and the profit share of GDP is still near record highs. If any one of these magnitudes reverts to its historic mean, EPS are likely to drop; if they all revert in tandem, the drop will surely be steep; and with the fear index at record highs, a significant earnings drop is almost certain to trigger a new MBM.

Either threat – a longer-term Iron Heel-like trajectory or a more immediate MBM – spells social turmoil. And sadly, progressive forces in the U.S. and elsewhere seem prepared for neither.

Endnotes

[1] Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan teach political economy at colleges and universities in Israel and Canada, respectively. All of their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (http://bnarchives.net). Research for this paper was partly supported by the SSHRC. The article is licenced under Creative Commons (Attribution-NonCommercial-NvoDerivs 4.0 International).

[2] In this article, we use ‘earnings’ and ‘profits’ interchangeably.

[3] See Núñez and Sweetser (2006) and Pincock (2006). To test this inverted perception, just look up at the stars: ahead of you you’ll see nothing but the past.

[4] The remainder of this article draws on, updates and extends aspects of our earlier paper.

[5] For a detail explanation and comparison with earlier formulations, see Bichler and Nitzan (2016: Section 6)

[6] The usefulness of a moving correlation here was suggested and shown by Ulf Martin in private communication.

[7] For example, the systemic fear index for September 2017 (last observation) is +0.50. This result is derived by averaging out the 120 monthly readings of the 12-month trailing correlations between August 2007 and September 2017.

[8] For a short history of capitalization, see Nitzan and Bichler (2009: Ch. 9).

[9] The word ‘nomos’ was used by the ancient Greeks to denote the broader social–legal–historical institutions of society (Castoriadis 1984, 1991). The capitalist nomos is explored in Nitzan and Bichler (2009: Ch. 9).

[10] This point was raised by Suhail Malik at the 2016 CasP conference presentation of this paper (http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/489/)

[11] For more on the asymptotes of power, see Bichler and Nitzan (2012).

[12] On the elementary particles of capitalization, see Nitzan and Bichler (Nitzan and Bichler 2009: Ch. 11)

[13] For the genesis, earlier versions and prior analyses of the MBM concept, see Bichler and Nitzan (2008), Kliman, Bichler and Nitzan (2011), Bichler and Nitzan (2012) and Bichler and Nitzan (2016) .

[14] The verb-noun ‘creorder’ fuses the dynamic and static aspects of creating order (Nitzan and Bichler 2009, especially Ch. 14).

References

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2006. Elementary Particles of the Capitalist Mode of Power. Paper read at Rethinking Marxism, October 26-28, at University of Amherst, Mass.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2008. Contours of Crisis: Plus ça change, plus c'est pareil? Dollars & Sense, December 29.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2010. Systemic Fear, Modern Finance and the Future of Capitalism. Monograph, Jerusalem and Montreal (July), pp. 1-42.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2012. The Asymptotes of Power. Real-World Economics Review (60, June): 18-53.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2016. A CasP Model of the Stock Market. Real-World Economic Review (77, December): 119-154.

Dalio, Ray, Steven Kryger, Jason Rogers, and Gardner Davis. 2017. Populism. Bridgewater Daily Observations (March 22): 1-61.

Gittelsohn, John 2016. Gross Trying to Short Credit to Reverse Decades of Instinct. Bloomberg, May 26.

Kliman, Andrew, Shimshon Bichler, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2011. Systemic Crisis, Systemic Fear: An Exchange. Special Issue on 'Crisis'. Journal of Critical Globalization Studies (4, April): 61-118.

London, Jack. 1907. [1957]. The Iron Heel. New York: Hill and Wang.

McKinsey & Company, Richard Dobbs, Anu Madgavkar, James Manyika, Jonathan Woetzel, Jacques Bughin, Eric Labaye, Liebeth Huisman, and Pranav Kashyap. 2016. Poorer Than Their Parents? Flat or Falling Incomes in Advanced Economies. McKinsey Global Institute (July): 1-99.

Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. 2009. Capital as Power. A Study of Order and Creorder. RIPE Series in Global Political Economy. New York and London: Routledge.

Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. 2014. Can Capitalists Afford Recovery? Three Views on Economic Policy in Times of Crisis. Review of Capital as Power 1 (1): 110-155.

Núñez, Rafael E., and Eve Sweetser. 2006. With the Future Behind Them: Convergent Evidence from Aymara Language and Gesture in the Crosslinguistic Comparison of Spatial Construals of Time. Cognitive Science: A Multidisciplinary Journal 30 (3): 401-450.

Ostry, Jonathan D., Parkash Loungani, and Davide Furceri. 2016. Neoliberalism: Oversold? Finance and Development (June): 38-41.