RESEARCH NOTE

Can Capitalists Continue to Squeeze the Income Share of Employees? [1]

Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan

Jerusalem and Montreal, November 2020

![]() bnarchives.net

/ Creative Commons

(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

bnarchives.net

/ Creative Commons

(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

There is much debate over the distributive share of employees in national income – how to measure it, whether it goes up or down and, of course, why it matters. But something in this debate often seems amiss. Like many aggregates, the national income share of employees is a synthetic measure. It’s made up of two largely unrelated entities – the relative number of employees in society and their relative individual income – and these two entities don’t have to move in the same direction. Indeed, in the United States they have trended in opposite directions for almost a century.

In this short research note, which focuses on the United States, we examine these opposite movements, explain why they are important and suggest that, if they continue, the United States will be much more conflictual and crisis prone in the future than it is today.

The Aggregate Picture

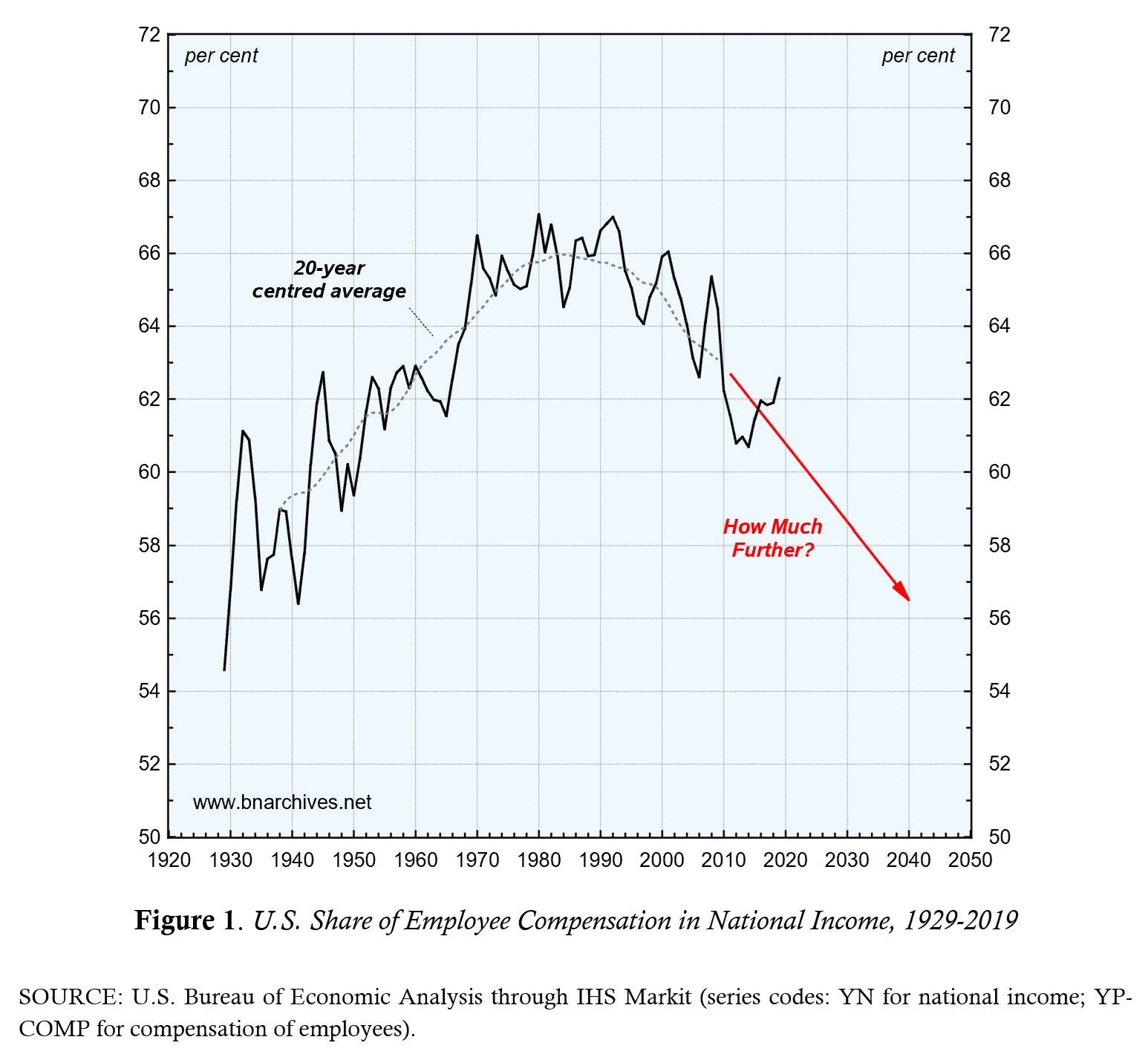

Figure 1 shows the historical evolution of overall employee compensation, expressed as a share of U.S. national income. The data cover almost a century, from 1929 to 2019, and the overall path traces an inverted U, shown by the 20-year centred average. Concretely, up until the early 1970s, U.S. employees saw their overall wages, salaries and supplementary income rise as a proportion of national income, making many analysts, including heterodox ones, worry about a ‘profit squeeze’; however, from the early 1970s to the early 1990s, the increase levelled off; and in the early 1990s, it became a downtrend that has continued till the present.

Based on Figure 1, it may be tempting to conclude that U.S. employees can be squeezed much further (downward arrow). It is true that their the current income share (as of 2019), standing at nearly 63 per cent of national income, is lower than it was in 1990 – but this share is still much higher than it was a century ago. And if the power of capitalists continues to increase, as it has since the onset of neo-liberalism, there seems to be no reason why this share cannot be pressed down even further.

Disaggregation

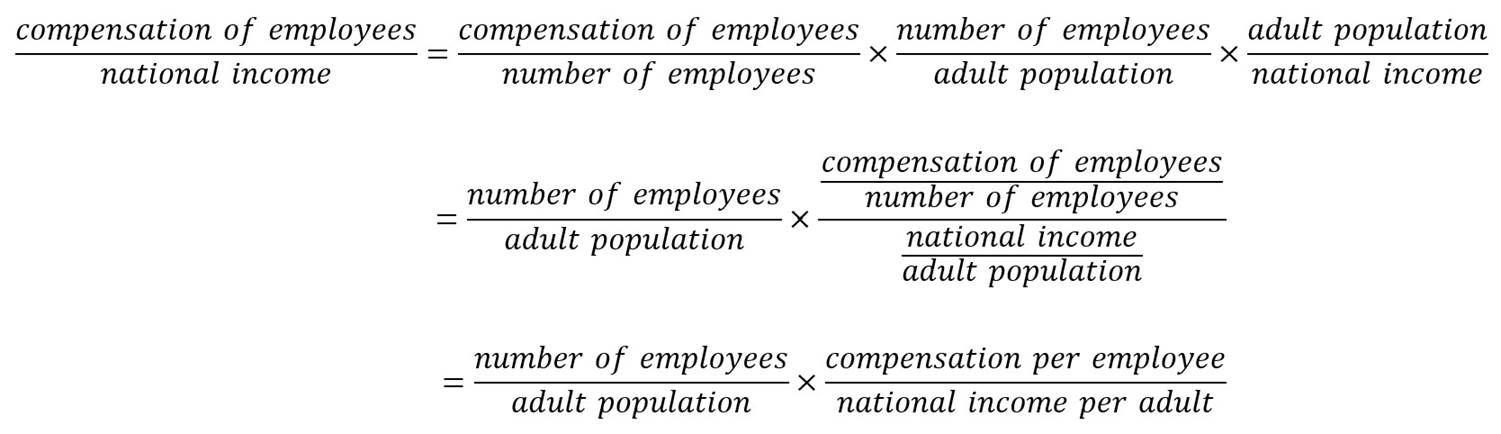

This conclusion, though, might be blinded by aggregation. The mathematical identity below shows that the share of employees in national income is a product of two distinct factors: (1) the share of employees in the total adult population; and (2) the ratio between compensation per employee and the national income per adult.

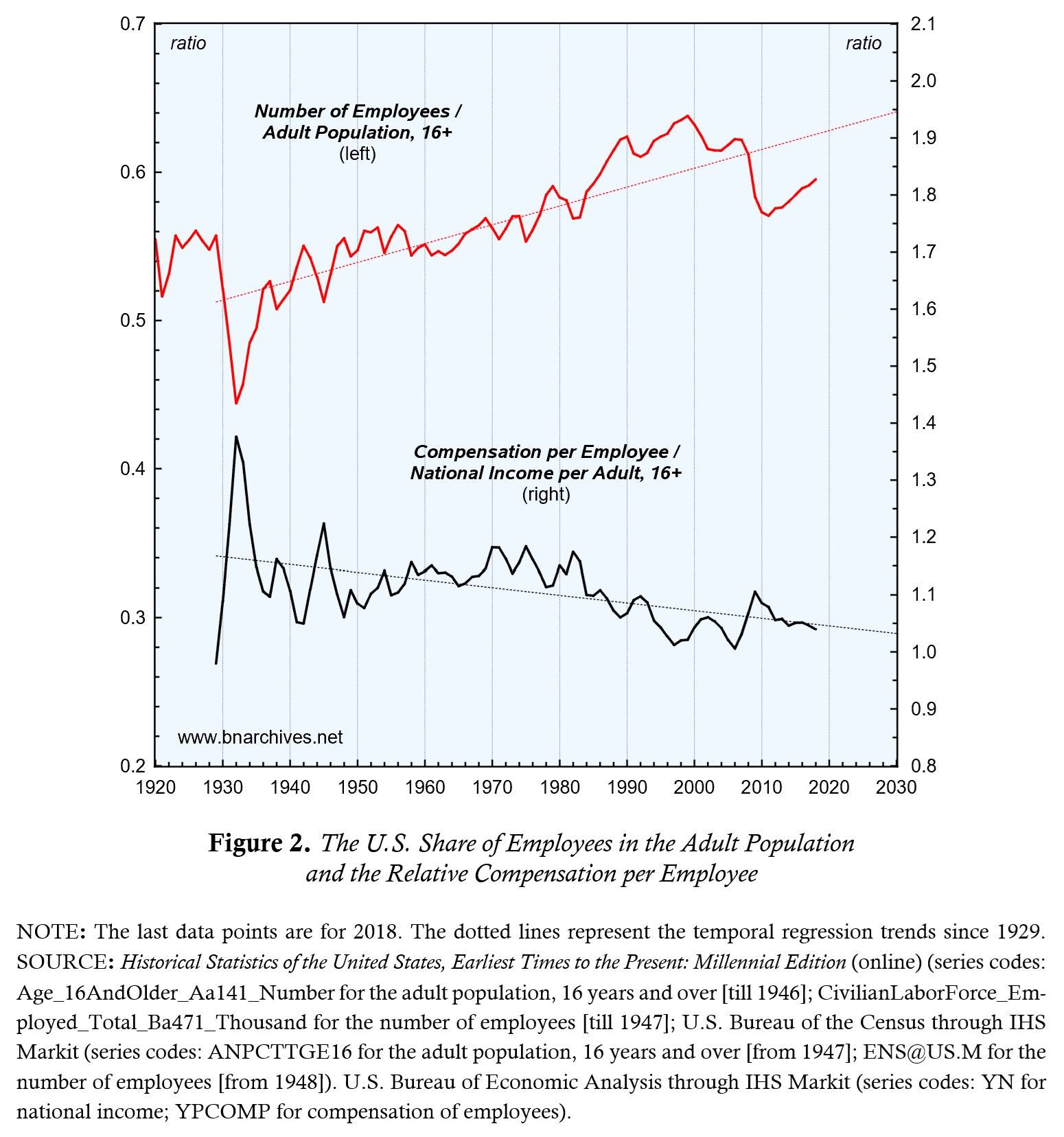

This decomposition is important because, as Figure 2 demonstrates, these two factors trended in opposite directions: over the past century, the first moved up and the second down. [2] And this opposite movement suggests that lowering the overall share of employees in national income may be far harder than it initially seems.

Analysis

Let’s examine our decomposition a bit further. The first factor – the share of employees in the total adult population, expressed as a decimal – measures the number of employees relative to all potential employees. The second factor – the ratio between compensation per employee and the national income per adult, also measured as a decimal – contrasts the average income of an employee with the average income in the entire adult population.

This decomposition means that, in principle, the income of employees can be redistributed in favour of non-employees in two ways. One is to convert workers into capitalists or proprietors of various sorts and redesignate their income accordingly. When this conversion happens, employee compensation becomes profit, interest, rent, entrepreneurial income, etc. – depending on the new identity assumed by the former employees.

But as the top series in Figure 2 shows, historically this conversion has gone in the opposite direction. Instead of seeing employees becoming capitalists, rentiers and self-employed, we observe that more and more capitalists, rentiers and self-employed have become employees. In the land of unlimited possibilities, opportunity beckons but its probability doesn’t knock.

The second way to redistribute income away from employees is to squeeze their average income relative to the average income of non-employees. According to the bottom series in Figure 2, this is precisely what has happened for almost a century: the average income of employees, measured relative to the national income per adult, has trended downward.

These opposite historical trajectories suggest that, in practice, capitalists have not two options, but one. The ongoing consolidation of capitalist power means that more and more small capitalists and self-employed persons – as well as future cohorts of new adults – will be forced to become workers. And if the top red line continues trending upward, capitalists will be facing a stronger and stronger headwind: everything else remaining the same, the relative bulging of the employee population will make their share of national income go up and up.

With this headwind in mind, the only way for capitalists to squeeze the overall income share of employees is to continue reducing the compensation per employee relative to the national income per adult – and to do so at an accelerated pace.

And this is where the going will get tough. Given that the ratio between compensation per employee and the national income per adult has trended downward for nearly a century, making it go down even further is likely to become harder and harder. It will require greater threats, larger doses of violence and the incitement of more and more fear. And since a greater exertion of power invites greater resistance, there is also the prospect of a powerful backlash. In this sense, the overall power of capitalists relative to employees might be much closer to its asymptote than the naïve picture in Figure 1 might imply. And if that proves to be the case, Trump is only the beginning.

Endnotes

[1] The argument and data in this research note are updated from our 2012 paper ‘The Asymptotes of Power’, Real-World Economics Review, (60, June): 18-53.

[2] Our emphasis here is on the long-term trends of the two series. Note, though, that their short-term fluctuations are also inversely correlated. When the political economy goes into recessions, employment falls relative to the adult population, causing the top series to decline. The average compensation per employee, though, does not tend to drop – and if it does, the drop is usually smaller than the decline in the average income per adult – which causes the bottom series to rise. The same counterforces operate in a boom – only in reverse.