Many

observers of the Israeli scene have been perplexed by the country’s

apparent resilience to bad political news. The headlines of late seem

uniformly dreadful. While the country is still licking its wounds from

a botched, if not humiliating, war with Hezbollah, the Palestinian

territories again slide into turmoil, and the experts rumour yet

another conflict with Syria . The U.S. entanglement in Iraq and

Afghanistan is only getting deeper, and many speak of an imminent

attack on Iran with untold regional consequences. Israeli politicians

and public officials – from the president, through the prime minister,

to the chief of staff, to the justice minister – have been embroiled in

corruption and other scandals. The courageous capitalist media

routinely expose government officials as incompetent crooks and the

Israeli Parliament as an irrelevant institution.

And yet none of these headlines seem to impact the economy. It’s roaring.

Local

commentators have been trying to make sense of this apparent puzzle for

over a year now. Most point to the effect of liberal globalization. The

long fight for sound finance, they say, is finally bearing fruit. The

government was forced to rein in its spending, and the consequent

emergence of budget surpluses now helps free scarce resources for more

productive private use. In parallel, free trade and capital decontrols

attract global investors, while allowing Israeli capitalists to link up

with the rest of the world. Laissez faire has arrived in the

Holy Land

: the country’s political folly and its security roller coaster no longer matter for its ‘economy.’[1]

Foreign analysts offer other explanations. For Thomas Friedman of The New York Times, the secret lies in the Israeli genius.[2]

The imagination, innovation and flexibility of the country’s citizens,

bolstered by higher education and government support for

entrepreneurship, help Israel adjust and respond to an ever-changing

world. Prosperity, according to Friedman, comes from the head.

Social critic Naomi Klein snubs Friedman.[3]

Israel ’s soaring stock market and China-like growth rates, she argues,

are fuelled not by the country’s human capital, but by its mutating war

economy. Military calamities, terrorism and counterterrorism offer an

ideal environment for developing and testing weapons of oppression.

Israel has become a big laboratory for such weapons. It develops and

tests the hardware and software of violence – against its Arab

neighbours and against the Palestinian population – and then sells them

to the rest of the world. Economic prosperity thrives on political

crisis.

The Historical Context

These

explications, whether plausible or not, all fall into the same trap:

they believe the capitalist media. They rush to explain why the Israeli economy is roaring without ever stopping to ask whether it is roaring.

Granted,

the latter question is not as exiting as the former. But since everyone

seems to take the ‘boom’ for granted, we thought it might it be a good

idea to check the facts. Just to be on the safe side.

So, is the Israeli economy roaring?

Clearly,

the answer cannot be decided on the basis of last year’s performance or

the most recent quarter. Israel and the region have been in turmoil for

decades, so economic performance, too, must be put in historical

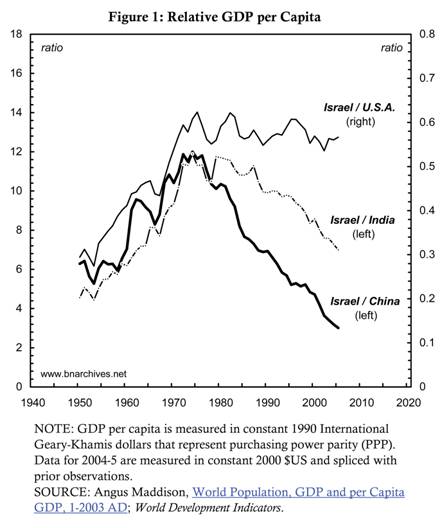

context. This is what we do in Figure 1.

The

chart focuses on GDP per capita, expressed in constant prices and

rebased to purchasing power parity. This measure is constructed in

several steps. First, the statisticians estimate, for every year, the

country’s gross domestic product, or GDP, expressed in prices

prevailing in some base year. This estimate – which economists call

‘real’ GDP – supposedly represents the aggregate ‘quantity’ of newly

produced goods and services (in contrast to ‘nominal’ GDP, which

represents both the prices and quantities of production).

Next,

the statisticians rebase the country’s ‘real’ GDP so it conforms to an

international standard of purchasing power parity (PPP). Since

different countries produce and consume different ‘baskets’ of goods

and services, their ‘real’ GDP levels are not readily comparable. The

purpose of the PPP conversion is to enable such comparison. To achieve

this conversion, the statisticians make the hypothetical assumption

that all countries produce the same international basket. They then impute to each country the level of ‘real’ GDP it could achieve if it were to produce not its own goods and services, but those included in the international basket.

Finally,

the statisticians divide the country’s ‘real’ GDP in PPP terms by the

size of its population. The result is GDP per capita in constant prices

expressed in purchasing power parity. Economists use this latter

measure to assess a country’s average productivity and average standard

of living – both over time and in comparison with other countries.

Before turning to the data, we should note that these conventional

measurements of ‘productivity’ and the ‘standard of living’ are highly

problematic, both conceptually and empirically. And the same is true

for the common emphasis on ‘aggregates’ and ‘averages’ – emphasis that

serves to ignore and conceal distribution and the underlying structure

of the political economy. We nonetheless stick here to standard

practices so that we can question the conventional creed on its own

terms.

Figure 1 compares the per capita performance of

Israel

with three countries:

China

,

India

and the

United States

. We do so by plotting three series, each of which expresses the ratio between

Israel

’s per capita GDP and the per capita GDP of one of these three countries.

The overall picture points to the mid 1970s as a clear watershed. During its so-called ‘socialist’ period,

Israel

outperformed. After the 1977 rise of Likud and the arrival of ‘liberalism’,

Israel

lagged.

The two lower series, plotted against the left-hand scale, track

Israel

’s performance relative to

China

and

India

. We can see that

Israel

’s per capita GDP was roughly 6 times

China

’s in the early 1950s, and that this ratio doubled, to about 12, by the mid 1970s.

From that point onward, though, the process inverted.

China

's per capita GDP soared,

Israel

’s lingered, and the ratio between them dropped precipitately. In 2005,

Israel

’s per capita GDP was only 3 times bigger than

China

’s, representing a four-fold relative decline since the mid 1970s.

A similar development, albeit less dramatic, is evident from the comparison with

India

. Here, too,

Israel

outperformed till the mid 1970s, after which the process went into reverse.

Seen

from this long term perspective, Israel ’s recent ‘boom’ – assuming

there is one – is a blip on a long term downtrend. Despite its three

decades of liberalisation, enterprising genius and military testing,

Israel hasn’t been able to deliver anything close to ‘China-like,’ or

even ‘India-like,’ growth rates.

Of course, one could reasonably contest this comparison. Obviously, it is misleading to contrast

Israel

– a mature capitalist society – with ‘emerging markets’ such as

China

and

India

.

But, then,

Israel

hasn’t done that well relative to mature capitalist countries either. The top series in Figure 1 shows the ratio between

Israel

’s per capita GDP and that of the

United States

, plotted against the right-hand scale.

Like with

China

and

India

, here too

Israel

outperformed till the mid 1970s and underperformed thereafter. Its per capita GDP fell from a high of 62 per cent of the

United States

’ in 1975, to 57 per cent in 2005.

Where Have All the Capitalists Gone?

So

there is nothing very miraculous about the Israeli economy. But, then,

this preoccupation with the ‘Israeli economy’ is itself misleading.

Measures

of national growth rates, GDP per capita, unemployment and the like may

be of great importance for most Israelis. But they are irrelevant for

Israeli capitalists.

There

are two main reasons for this assertion. First, and more generally,

capitalists are interested not in the growth of ‘material’ output and

the so-called ‘real’ capital stock, but in the expansion of their

financial assets. And as strange as it may sound, the ‘real’ world of

economic performance and the ‘nominal’ world of finance often are

unrelated and sometimes even move in opposite directions.[4]

Second,

and specifically for our purpose here, is the issue of identity.

Economic measures do not matter for Israeli capitalists simply because

there are very few ‘Israeli’ capitalists left.

Since

the early 1990s, the opening up of Israel , both outward and inward,

has created a massive flow of capital going in both directions. Global

investors, transnational corporations, Russian oligarchs and money

launders have all flocked into Israel . They bought up anything of

value – bonds and stocks, entire companies and prime real estate, sport

teams and local politicians. In parallel, domestic capitalists have

diversified abroad: they took the proceeds of their local divestments

and invested them outside Israel .

The

net result of this bidirectional process has been the disappearance not

only of the ‘Israeli’ capitalist class, but also of ‘Israeli’ companies.

Nowadays, all the large capitalists who happen to live in

Israel

(at least part of their time) have global investments that often eclipse their holdings in

Israel

proper. And practically all the leading corporations located in

Israel

are transnational – in operations, ownership, or both.

In

other words, the issue is not that Israeli accumulation has become

indifferent to Israeli politics, but rather that Israeli accumulation

has become less and less ‘Israeli.’

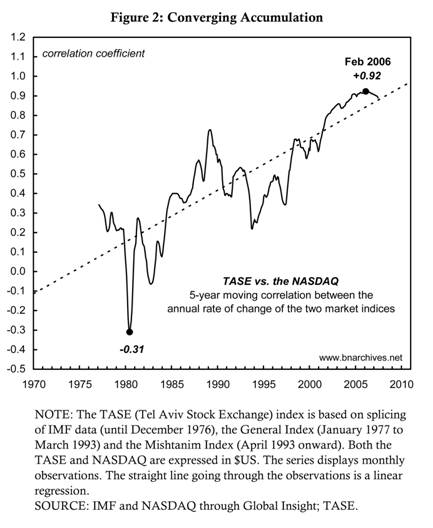

The

consequence of this transnationalization of ownership is illustrated in

Figure 2. The chart correlates the annual rates of growth of the Tel

Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE) and of the NASDAQ (with underlying monthly

data denominated in $US). Each point in the series represents the

correlation over the previous five years, with values ranging from a

minimum of –1 (indicating that the rates of growth of the two stock

markets move exactly in opposite directions), through a

mid-point of 0 (denoting that the two markets are unrelated), to a

maximum of +1 (when rates of growth move exactly in the same direction).

The

trend depicted in the chart is unambiguous. During the 1980s, the two

markets were more or less independent. The correlation between them was

low and often negative. But over time, and particularly since the early

1990s, the transnationalizaton of ‘Israeli’ capital and capitalists has

made the correlation tighter and tighter.

When we first plotted this relationship in 2001, the correlation coefficient approached 0.7. By 2006, it reached 0.92.[5]

In non-technical language, this latter number suggests that, over the

2001-2006 period, 92 per cent of the variations in the TASE could be

‘explained’ by variations in the NASDAQ (it would be difficult to argue

the opposite). And, indeed, since the two asset classes share similar

owners, have similar sources of earnings, and float in similar pools of

liquidity, there is really no reason why they shouldn’t move together.

Thus,

if the Israeli stock market is currently booming, it is not because of

or despite the ‘political situation.’ It booms for the same reason the

NASDAQ does. And if and when the TASE takes a nose dive, again, don’t

look for local or regional explanations. Just check the NASDAQ.

Of

course, Israeli politics continues to matter in many different ways. It

matters to the companies listed in Tel-Aviv insofar as it guarantees

that the stock market can open every morning, and that their Israeli

operations can function without hindrances. Domestic politics also

matters insofar as it affects Middle East developments, and hence

global accumulation, the NASDAQ and, therefore. . . the TASE.

But formal politics matters not because it is public. It matters precisely because it is anti public.

As long as the country’s patriotic ‘politicians’ and ‘public officials’

remain obedient to capital in the name of democracy, and as long as the

cost of bribing them remains reasonably low, the resulting boom of

private accumulation will remain mysteriously ‘delinked’ from the

fracturing of public life and the disintegration of autonomy and

democracy.

Jerusalem and Montreal, June 2007

http://www.bnarchives.net/

Notes

[1] Nechemia Strassler, Buy Me Gaidamak, Hebrew. Ha'aretz, June 13, 2007.

[2]

Thomas Friedman

,

Israel

Discovers Oil, The New York Times, June 10, 2007.

[3] Naomi Klein, How War was Turned into a Brand, Guardian, June 16, 2007.

[4] See our recent Hebrew monograph, The Gods Failed, the Priest Lied, May 2007, and the more general discussion in our Elementary Particles of the Capitalist Mode of Power, October 2006.

[5] For the early estimates, see Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler, The Global Political Economy of Israel,

London

: Pluto Press, 2002, Figure 6.6, p. 355.

News

News  English Articles

English Articles  Israel's Roaring Economy

Israel's Roaring Economy