From Welltop to Laptop?

Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan

In ‘Dominant Capital and the New

Wars’, an article that we wrote in October 2002 and later published in the Journal

of World Systems Research (2004), we argued that the global regime of

accumulation was undergoing a major change. Instead of the mergers and

acquisitions that fuelled the breadth phase of the 1980s and 1990s, dominant

capital was moving toward a depth phase of stagflation and crisis. The new wars

in the

Back then, our prediction and reasoning were greeted with indifference. The general mood was deflationary, and the experts preferred to analyze the post-invasion dismantling of OPEC and the coming of dirt-cheap energy. But the times, they are a’changin’, and the pundits are quick to adjust. With crude petroleum hovering around $125 per barrel and raw material and food prices having doubled, even the backward-looking IMF now feels it safe to cry inflation.

So far, though, soaring commodity prices have had a relatively minor impact on the overall level of prices, at least by historical standards. Whereas oil is twelve times more expensive now that it was in 1999, consumer prices in industrialized countries are only 20 per cent higher.

The question, therefore, is why the sluggish response? What is it that prevents rapid inflation from taking hold? One important reason lies in the nature of profit expectations. As we explained in ‘Dominant Capital and the New Wars’,

. . . rising inflation is not very different from an investment-led boom. There is little to prevent any individual firm from building new capacity. But for firms to actually go ahead and install new factories, they need to believe that this new capacity will increase profit in the future; and that belief is most likely to trigger action when it is commonly shared. In other words, it is only when many firms begin to view green-field investment favorably that individual companies begin to spend money on new plant and equipment. Once the process is set in motion, increases in production, income and spending make these profit expectations self-fulfilling, but the initial spark usually requires a change in the broad outlook of companies.

A similar process unfolds when inflation begins to accelerate. As more and more firms start raising prices, and as income begins to be redistributed from workers to firms . . . and from smaller to larger ones . . . expectations for differential inflationary profits are ‘validated,’ leading to even more price hikes. But like with investment, here, too, in order for the process to begin, there needs to be a common expectation, a shared view among the dominant groups in society, that inflation will boost their differential profit. (2004: 297)

By early 2003, the imperative of inflation was already clear, at least at the apex of the accumulation structure:

‘Greenspan must

go for higher inflation,’ insist Bill Dudley of Goldman Sacks and Paul McCulley of Pimco in a recent Financial

Times article. ‘Inflation is too low, rather than too high,’ they warn, and

‘the Fed should welcome a modest rise in inflation’. . . . And

it is not as if the Fed has not been trying. Over the past two years Alan Greenspan

has cut interest rates to levels last seen in the happy 1960s, making money

cheaper and cheaper. Fear of deflation is finally creeping into the Fed’s own

statements. In a recent announcement, Greenspan warned of ‘unwelcome

substantial fall in inflation’. . . . That is probably the first

time since the Great Depression that the

The spark was lit by the

Whereas leading strategists were quick to grasp the need for a pro-inflation outlook, rank-and-file executives fighting in the business trenches were still locked in a different mood. Most corporate officers under the age of 50 have come of age in a world defined by the experience of disinflation. Shaped by this backdrop, their common belief is that profit depends on cutting cost and lowering prices. And it is this widespread outlook that needs to change for inflation to start in earnest.

Inflation started to decline as the globalization of ownership began to gather momentum in the early 1980s. The process was driven by two related transformations: (1) a shift of manufacturing from developed to developing countries, where wage costs are significantly lower; and (2) rapid technical change – particularly in the areas of computing, telecommunications and information technology – which in turn contributed to the progressive cheapening of equipment and consumer goods.

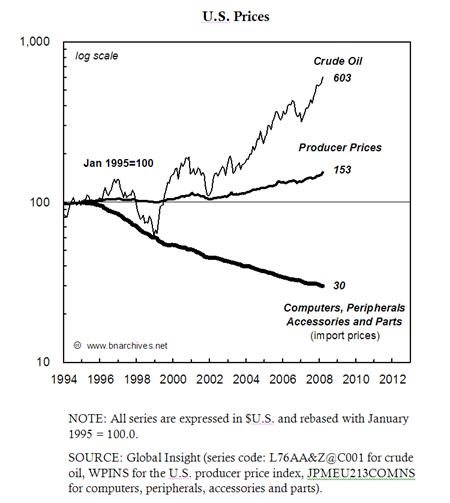

The consequences of this dual transformation are illustrated in the

enclosed figure. The chart shows three price series: the

As the data show,

since January 1995 the price of crude oil rose by a factor of six (and by much

more from its 1999 low). The average level of producer prices, however,

increased by only 53 per cent. The reason for this limited response is

suggested by the shape of the bottom series. In contrast to the soaring price

of oil, the price of computers and related equipment dropped precipitately – by

as much as 70 per cent during the period. This ongoing deflation, typical of

many imported manufactured commodities, has worked to counteract the soaring

cost of energy.

But now the

writing is on the wall. Last week, a Financial Times article titled ‘Laptop Retail

Prices Forced Up’ (

The language is certainly new. It suggests that ‘high-tech’ companies, the white knights of the ‘new economy’, are now openly talking about – not to say colluding over – price increases. Furthermore, their deliberations concern commodities whose prices have always fallen. If there is a sign that dominant capital is finally gearing toward inflationary profit, this must be it. And if this shift proves significant enough, the wrath of inflation may still be upon us.