Research Note

Capitalizing Obesity

Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan [1]

Jerusalem and Montreal, April 2016

bnarchives.net / Creative Commons

![]()

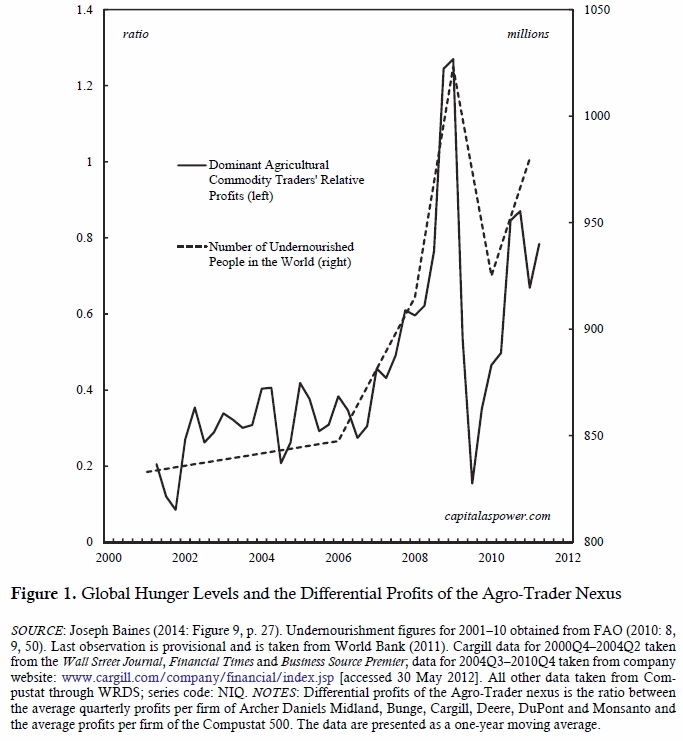

In his article, ‘Food Price Inflation as Redistribution’, Joseph Baines (2014) shows the intimate correspondence between differential profit and world hunger. Figure 1 below, reproduced from his article, portrays a systematic positive correlation between the relative income of the Agro-Trader Nexus (Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, Deere, DuPont and Monsanto) compared to the Compustat 500 on the one hand and the number of undernourished people in the world on the other.

The Other Side of Hunger

But the capitalization of food is a dialectical process. As Michael Harrington noted more than half a century ago in his seminal book The Other America (1962), the other side of affluence is poverty; and among the American poor, the other side of hunger is overweight and obesity.

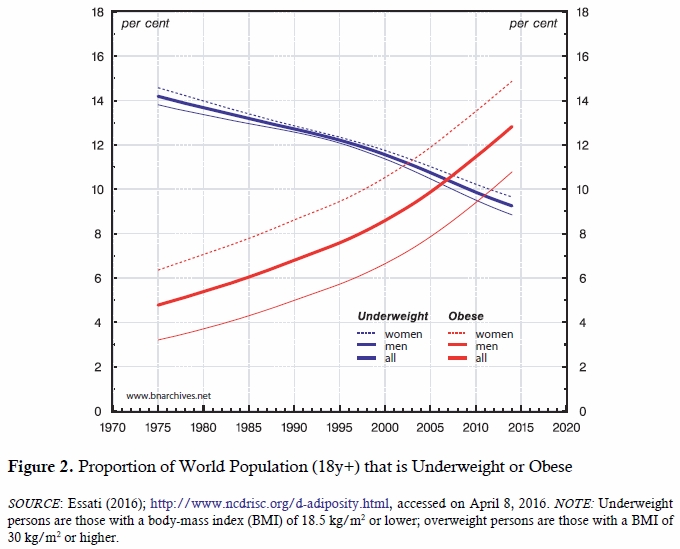

Fifty years later, Harrington’s insight has grown into a global menace (for a detailed overview, see Albritton 2009). Figure 2 shows data from a long-term study published in The Lancet (Essati 2016). The data demonstrate that, for the first time in history, there are now more obese than undernourished people in the world (roughly 13% compared to 9% as of 2014), and it suggests that, looking forward, obesity is likely to pose a far greater health hazard than undernourishment. (Note the gender dimension: women tend to suffer more than men from both undernourishment and obesity, but the female-male disparity in the latter predicament is much greater than in the former.)

There is a fundamental biological difference between undernourishment and obesity: while hunger drives the undernourished to eat more if they can, there is no parallel instinct propelling the obese to eat less. On the contrary. The human body, having evolved during the long Palaeolithic epoch of hunting and gathering, craves salt, sugar and fat. But this very craving – which was necessary for survival in Palaeolithic times – became destructive once salt, sugar and saturated fat grew abundant (Harris 1989; Diamond 2012: Ch. 11). And because humans have limited natural defences against their own cravings, obesity is now an easier to inflict – and potentially more profitable – form of capitalized sabotage than undernourishment ever was. So, in the end, although undernourishment and obesity are biological opposites, they share a basic social similarity: they are both instruments of power.

Power in Hunger

Hunger has been a central lever of power throughout history. The earliest state civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt were made possible, first and foremost, by the domestication of grains, particularly barley. The abundance of grains produced by the workers and slaves of these societies helped sustain a triangular complex of palace-temple-army, which in turn fed and provided for – as well as threatened, organized and ruled – their underlying propertyless populations. The central role of food in this process is imprinted all over the artistic carvings and drawings of these early societies: they portray their rulers as large, weighty and often overwhelming, while the ruled are shown as small, skinny and hunched over.

The Middle Ages too were organized around food. In the feudal regimes of Europe and Japan – as well in the empires of China, the princely states of India and the caliphates of the Middle East – the rulers controlled the land or its produce, and, by extension, the peasants who cultivated it. Their main threat was expulsion or extraction: for the tillers, being kicked off the land or deprived of its crops often meant hunger, privation and early death.

The transition to capitalism didn’t change the basic equation, at least not initially. The new liberal individual was obsessed with income and wealth; but the reason for this obsession was still the looming threat of poverty and hunger – the ultimate ‘scarcity’ of the capitalist universe. According to many, it was the permanent threat of hunger, amplified by a growing enclosure movement, that propelled the feudal population into the burgeoning cities, thus kick-starting urbanization and helping usher the Industrial Revolution. Hunger also anchored the classical political economy of Ricardo, Malthus and Marx, where the value of commodities was said to hinge on subsistence wages. And if we are to judge by the era’s novelists – from Balzac and Dickens to Hugo, Zola and Maupassant – the menace of hunger remained front and centre throughout the Victorian era. In the visual arts, the rulers, just like in antiquity, were portrayed as fat, healthy and long-living, while the ruled appeared underweight, sickly and ready to die.

Communism too was ruled by hunger. The Russian and Chinese revolutions were supposedly fought for human liberty and dignity. But as the communist masses were soon to learn, their new historically materialistic rulers – much like their divine predecessors – were particularly keen on leveraging the caloric intake of their subjects, usually to the latter’s detriment. Those who didn’t comply ended up in labour camps and other correctional facilities, where meagre portions of wheat and rice spelt want, sickness and doom – and all that while their rulers, generals and bureaucrats, like oriental despots, displayed their opulent bodies and multiple chins in official speeches and victory parades.

Twentieth-century capitalism promised an end to this spectre of hunger. The classical subsistence-wage labourer was replaced by a rational neoclassical ‘agent’. Having climbed out of poverty, the new ‘representative’ agent was no longer content with little food and shabby shelter; he or she became a ‘sovereign consumer’ determined to maximize his or her individual ‘utility’. Later on, with the spreading ritual of capitalization, the neoclassical agents were again remodelled – this time as walking ‘human capitals’ set on augmenting their ‘net worth’. The lives of these agents are still driven by ‘scarcity’, or so they are being told. They remain haunted by unlimited wants far exceeding their limited resources, and they still fight for ‘survival’. But unlike before, their fight now is said to be fuelled by the fervour of greed and the fear of being left behind, not by the threat of hunger and the prospect of extinction.

Power in Obesity

But this sea-change hasn’t eliminated food as a key lever of power. Far from it. Food is still a crucial form of social control – only that now it comes in a very different guise. Whereas until recently – and even today in parts of China, South Asia and Africa – the main threat for the underlying population was having too little to eat, nowadays it is having too much. The poor, traditionally punished by hunger, are now much more likely to be penalized by obesity.

This massive, ongoing transformation is reshaping the heart, mind and body of the capitalist subject. The undernourished, underweight, work-till-you-drop poor are gradually being replaced by their overfed, overweight, shop-till-you-drop descendants. And this inversion is hardly for the better. Although the adipose poor live longer than their scrawny predecessors, they are not necessarily healthier. They tend to suffer from non-communicable diseases – primarily diabetes, hypertension, strokes, cancer, heart attacks, atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular ailments (Diamond 2012: Ch. 11). And having been born into a hyper-capitalized complex of cheap industrial food, accessible pharmaceutical drugs and a highly intoxicating mass media, many of them are gradually losing their ability to control their inflating bodies and liberate their captured souls.

Ironically, this obesity revolution has been driven by wheat, rice, corn and potatoes – the very same crops that leveraged food power in the earlier hunger era. The plants that forced and lured hunters and gatherers into centralized state structures are now used – together with numerous supplements, both chemical and mental – to enslave capitalist subjects to their own irresistible cravings. And as the sedated, junk-food eating subjects become bigger and heavier, their previously ‘fat cat’ capitalist rulers eat organic, go to the gym and grow leaner and meaner. . . .

The Questions

There is nothing automatic, let alone natural, about this dialectic of food, poverty and power. The intertwined evolution of hunger and obesity is intimately connected to differential profit and accumulation. Both hunger and obesity represent complex levers of strategic sabotage, both get capitalized, and therefore both can be examined qualitatively and quantitatively. The capitalized dollar magnitude of this process – involving food, energy, pharmaceuticals, advertising and the mass media to the tune of trillions – makes it one of the key processes of modern capitalism, and therefore crucial to understand.

How has this remarkable hunger-to-obesity transformation evolved? What forms of capital drive the obesity epidemic, including its counter-movements of anti-obesity drugs, non-communicable disease treatments, diets, surgical fixes and psychological interventions? What are the material/ideal technologies that shift the world toward ever more destructive yet profitable forms of mass overfeeding? What policies and legislation have supported this shift, and how have they been imposed on the world’s population? And most importantly, what are the qualitative and quantitative links, if any, between these various strategies of sabotage on the one hand and differential profit and capitalization on the other?

Endnotes

[1] Shimshon Bichler teaches political economy at colleges and universities in Israel. Jonathan Nitzan teaches political economy at York University in Canada. All of their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (http://bnarchives.net). Research for this article was partly supported by the SSHRC. The article is licenced under Creative Commons (Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 Canada).

References

Baines, Joseph. 2014. Food Price Inflation as Redistribution: Towards a New Analysis of Corporate Power in the World Food System. New Political Economy 19 (1, January): 79-112.

Essati, Majid, et. al. 2016. Trends in Adult Body-mass Index in 200 Countries from 1975 to 2014: A Pooled Analysis of 1698 Population-Based Measurement Studies with 19·2 Million Participants. The Lancet 387 (10026, April 2): 1377-1396.

Harrington, Michael. 1962. The Other America. Poverty in the United States. New York: Macmillan.