Wars have become too cheap to boost growth

from Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan

This week, with the Federal Reserve Banks of New York and Atlanta anticipating sharply lower GDP growth for 2019:Q1, President Trump presented a ‘Budget for A Better America’, calling for a smaller government and a bigger military.

Forty years ago, the very same call was hailed as the best recipe for renewed growth. The U.S. ruling class was getting ready to install Ronald Reagan as President, abandon the Cold War and embark on neoliberalism, and it argued that, for that shift to succeed, the country needed a leaner government in order to unleash its entrepreneurial spirit and crowd-in private investment, and that it required a strong military in order to boost its global muscle and open world markets for its products and capital.

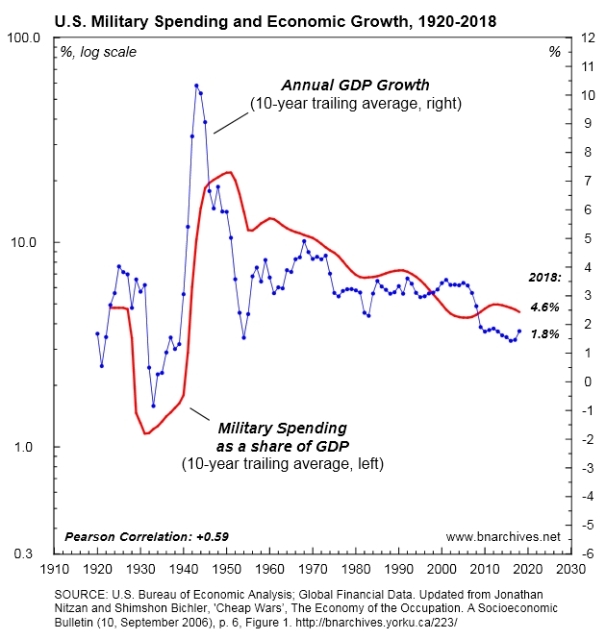

Ideology aside, one key reason for the growth optimism of the time was rising military spending: as the enclosed figure suggests, over the past century U.S. GDP growth has moved in tandem with the GDP share of military spending (Pearson Correlation Coefficient = +0.59).

This positive correlation continues to hold in Trump’s world – with an important caveat. While the absolute dollar size of the country’s military budget today is larger than ever, its GDP share is smaller than at any time during the post-war era: from 1991 to 2018, military expenditures amounted, on average, to 4.7% of GDP – compared to an average of 9.4% between 1950 and 1990.

Now, if the correlation shown in the chart isn’t spurious – in other words, if higher U.S. growth indeed depends on a larger share of the country’s GDP going to the military – America’s growth prospects look dim.

And the reason is simple: military spending has become increasingly difficult to raise, even for an autocratic president like Trump.

The ongoing development of military technologies and the increasing destructiveness of modern weapons have made contemporary wars – particularly against lesser enemies – progressively cheaper to prepare for and fight (note how the massive entanglement in Iraq and Afghanistan created no more than a blip on the red solid series). And as the means of destruction grow evermore potent and the cost of killing, maiming and incapacitating fall lower and lower, the ability of U.S. governments to justify and legitimize higher military spending declines.

A nice illustration of the folly of using GDP as a measure of anything desirable.

Let’s spend money blowing things up because that will boost “the economy” (meaning the GDP).

Let’s pay someone to dig holes and someone else to fill them in again. It would boost “the economy”. At least it wouldn’t cause any harm.

Interestingly, since about 1998, GDP growth and percentage of military outlays seem to be negatively correlated, whereas prior to that period they seemed to be always positively correlated.

This can be observed visually on the chart and would require some numerical confirmation, but it could indicate that something fundamental changed during the 1990s — in the composition of the GDP, or in the way the USA wage wars.

You may be demanding too much from a century-long +0.59 correlation coefficient. The late 1940s and then the late 50s early 60s are similar patches of inverse correlation.