Carrying the Elephants

Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan [1]

Jerusalem and Montreal, August 2022

![]() bnarchives.net / Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

bnarchives.net / Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

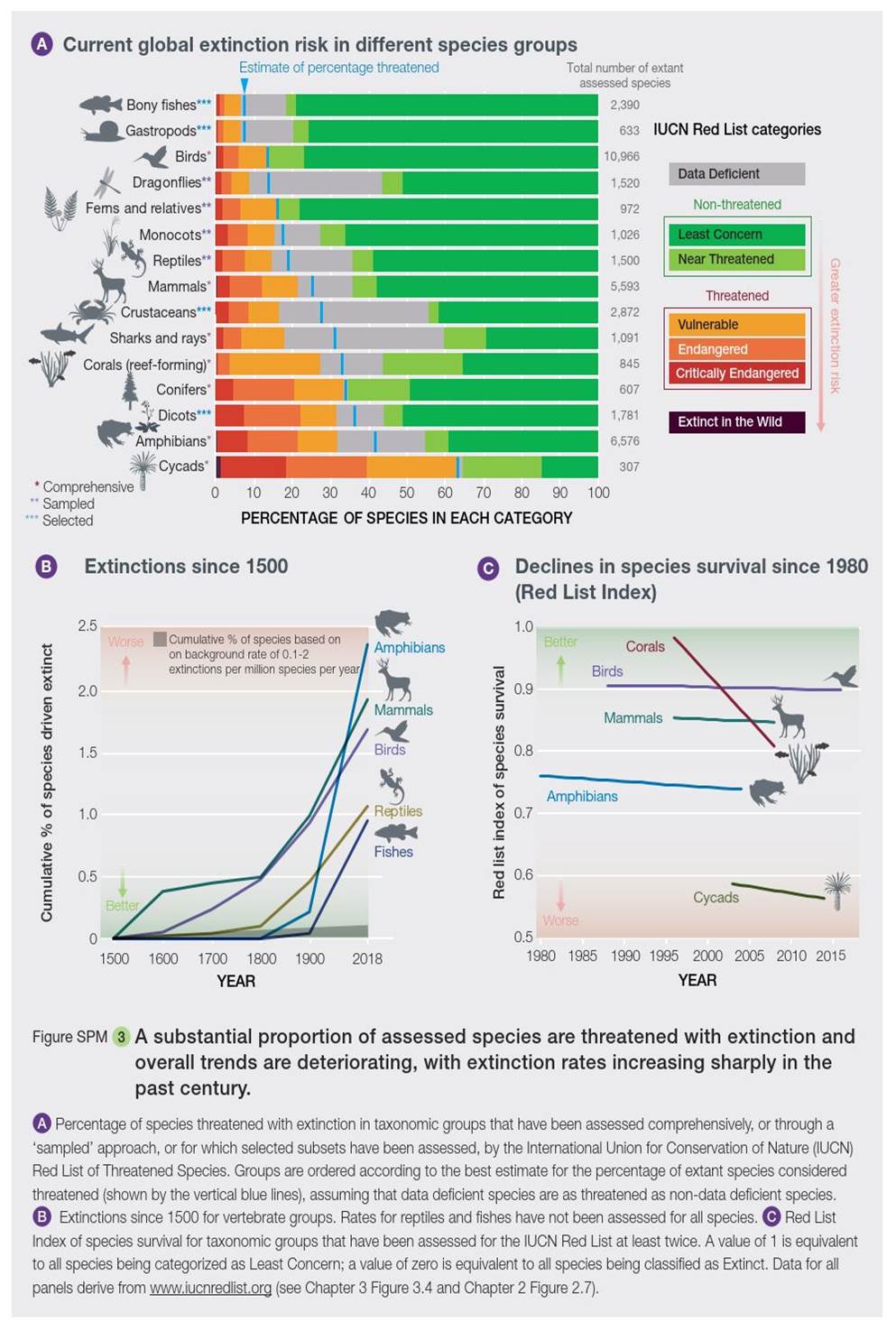

The big picture is unambiguous: humanity is undermining the planetary ecosystem, and the deterioration continues unhindered. According to the 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, since 1970, the capacity of nature to sustain contributions to good quality of life trends downward in 14 out of 18 different categories being analysed (first figure, from Page XXVII of the report), with many species dwindling or becoming extinct (second figure, from Page XXX). And if this isn’t enough, the burning of fossil fuels is believed to alter the climate, most likely for the worse.

At stake, then, is the survival of planetary life as we know it, humanity included. And in this dire context, it is worthwhile reading Romain Gary’s great 1956 novel, The Roots of Heaven (translated into English in 1958). This Goncourt Prize book is one of the first ‘ecological novels’. It tells the story of a Frenchman, Morel, a former concentration-camp prisoner and decorated war hero on a mission to save the hunted elephants of Africa.

It is a complex, intellectually

gripping story, weaving key issues of the time – from postwar global politics

and the nuclear arms race to the clash of colonialism and liberation movements

to culture, religion and philosophy – and its broad sweep is narrated with the

sensitivity, irony and occasional wishful thinking of a great humanitarian.

It is a complex, intellectually

gripping story, weaving key issues of the time – from postwar global politics

and the nuclear arms race to the clash of colonialism and liberation movements

to culture, religion and philosophy – and its broad sweep is narrated with the

sensitivity, irony and occasional wishful thinking of a great humanitarian.

And it is this emphasis on humanity that makes the book so important.

Morel’s stated mission is saving the elephants, hunted for ivory and thrill by the whites and protein by the blacks. But his deeper purpose is the soul and freedom of humanity itself.

The concentration camp taught Morel about loneliness and despair – but also about the liberating power of compassion. In captivity, the inmates invented a woman figure, so they can care for her – figuratively speaking – to maintain their own dignity; they insisted on helping little beetles back on their legs; they imagined hundreds and thousands of elephants roaming freely. . . . Compassion kept them humane, and there was nothing their Nazi guards could do to take that humanity away.

‘Man on this planet’, writes Gary, ‘has reached the point where really he needs all the friendship he can find, and in his loneliness he has need of all the elephants, all the dogs and all the birds. . . .’ (36).

Utilitarianism is never enough; in fact, left on its own, the quest for utility quickly becomes a menace:

It’s absolutely essential that man should manage to preserve something other than what helps to make soles for shoes or sewing machines, that he should leave a margin, a sanctuary, where some of life’s beauty can take refuge and where he himself can feel safe from his own cleverness and folly. Only then will it be possible to begin talking of a civilization. A utilitarian civilization will always go on to its logical conclusion – forced labor camps. (66-67)

And it's not only nature itself. It is the very caring for nature that humans really crave for:

Islam calls that ‘the roots of heaven’, and to the Mexican Indians it is the ‘tree of life’ – the thing that makes both of them fall on their knees and raise their eyes and beat their tormented breasts. A need for protection and company [. . .] for justice, for freedom and dignity – are roots of heaven that are deeply imbedded in our hearts. . . . (183)

In this respect, the purely technical aspects of development are highly precarious. The only way to truly develop is ‘not only to move forward but to encumber ourselves with the elephants as well, take a weight of that size along on the journey’ (214).

Unless we carry the elephants on our backs, writes Gary, development – in Africa and elsewhere – is bound to become destructive, not only of nature, but of our own human autonomy:

One day they’ll have their Stalins, their Hitlers, and their Napoleons, their Führer and their Duces, and then their very blood will cry out to demand respect for nature. That day they will understand. (254)

But then it will be too late.

Endnotes

[1] Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan teach political economy at colleges and universities in Israel and Canada, respectively. All their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (http://bnarchives.net). Work on this research note was partly supported by SSHRC.

References

Brondizio, Edwardo Sonnewend, Josef Settele, Sandra Diaz, and Hien Thu Ngo, eds. 2019. The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany: Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

Gary, Romain. n.d. The Roots of Heaven. Translated from the French by Jonathan Griffin. New York: Pocket Books Inc. (Originally published in 1958 by Simon and Schuster).