Working Papers on Capital as Power, No. 2024/04, August 2024

The Road to Gaza, Part II: The Capitalization of Everything

Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan [1]

Jerusalem and Montreal

August 2024

bnarchives.net / Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Abstract

Our recent article on ‘The Road to Gaza’ examined the history of the three supreme-God churches and the growing role of their militias in armed conflicts and wars around the world. The present paper situates these militia wars in the broader vista of the capitalist mode of power. Focusing specifically on the Middle East, we show the impact these militia wars have on relative oil prices and differential oil profits and explain how the wars themselves, those who stir them and the subjects that fight them all get discounted into capitalized power.

1. Militia Conflicts

In our paper ‘The Road to Gaza’ (Bichler and Nitzan 2024) we pointed out that more and more conflicts and wars these days are waged between ‘private’ armies and militias; that these armed groups and militias are commonly backed and financed by states, religious NGOs and criminal organizations; and that they tend to fight for and against states, as well as each other.

The growing importance of militia wars, we further posited, is intimately tied to the gradual decline of the nation-state, whose structure and limited reach no longer resonate with the increasingly globalized capitalist mode of power. As a result of this decline, dominant capital now strives to replace the old model of representative democracies, ostensibly sanctioned by their individual citizens, with a new regime of oligarchic states legitimized by ‘big leaders’, capitalist heroes and racist ideologies. As this structural shift gains momentum, private forces and stand-alone militias gradually supplant the traditional ‘national army’ that originally grew out of the French Revolution. [2]

In the global periphery, where the nation-state has rarely developed fully, the disintegration flares up in multiple conflicts between regions, tribes, ethnic and church militias and criminal gangs. This process is prevalent across much of Africa, as well as in many parts of Central and South America, Asia, Eastern Europe and the Middle East. [3]

Currently, the most publicized hotspot in this process is the war that started in 2023 between Israel and Hamas/Islamic Jihad and later expanded to include also Hezbollah, the Houthis and Iran. Each side of this war is aligned with its own supreme-God church: Israel increasingly caters to and is guided by the Rabbinate church, while Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Hezbollah and their backers abide by its Islamic counterpart. [4]

The Rabbinate militias, embodied in Jewish settler organizations, have been operating for over half a century under the auspices of and with heavy financing from all Israeli governments (as well as from various neoliberal oligarchs and NGOs, local and foreign). These militias have managed to gradually capture Israeli society by the throat. Following the war of 1967, they have taken over more and more occupied Palestinian lands and, from the 2000s onward, seized key political parties, assumed control over large chunks of the media, penetrated and altered the education system, redefined the socio-political discourse and become a mainstay of the country’s civil service, security apparatuses and military. Looking forward, they plan to turn Israel – by force, if necessary – into a neoliberal-Rabbinate autocracy.

The mirror side of this process is the ascent of Islamic militias. The inability of the Palestinians to arrest, let alone reverse, the long Israeli occupation has caused their traditional resistance movements – mainly the PLO and the PFLP – to wither and the Palestinian Authority to weaken and grow more corrupt. The resulting void has been filled by armed Islamic militias – the Sunni Hamas and the Shiite Islamic Jihad. The former has been financed mainly by Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States, whereas the latter, along with Hezbollah, operate largely under the Iranian umbrella of the Ayatollahs.

On the face of it, this and similar militia conflicts – especially those supported and driven by the supreme-God churches – seem alien, if not antithetical, to the capitalist mode of power. Ideologically, capitalism is based on individualism, rationality and the pursuit of hedonic pleasure, whereas the supreme-God churches promote a rigid collectivist ethos, unquestioning belief in divine power and submission to prevailing hierarchies of state, church and patriarchy.

But this seeming contradiction is deceiving. First, and surprising as it may seem, the prevalence of church-based discourse does not contradict but resonates with key capitalist processes. Using data from Blair Fix (2022), we show in ‘The Road to Gaza’ how the use of biblical discourse, measured relative to the use of economic discourse, trended downward since the 17th century, and that this downtrend reversed, decisively, in 1980. From that year onward, the prevalence of biblical jargon in the Google book corpus of the English language soared, while the use of economic jargon plummeted.

Now, the interesting bit here is that this temporal V-shaped pattern of decline, reversal and resurgence reproduces, almost exactly, the one shown by the distribution of U.S. income and assets. The ratio between earnings per share and the wage rate, the income share of the top 1% and the wealth share of the top 1% all correlate positively and tightly with the changing relative importance of biblical jargon: all three measures declined till 1980 and surged from then onward (Bichler and Nitzan 2024: Figures 1 and 2).

The reason for this co-movement is not difficult to fathom. As long as income and asset inequality declined, liberal ideals of enlightenment, progress, rationality and equality seemed congruent with and served to bolster the capitalist regime. But with inequality and its associated sabotage increasing – as they have since 1980 – the discourse had to change. And that is where the biblical jargon of hierarchy, submission and acceptance came in handy.

The second, more general reason why church-bound conflicts – and militia conflicts more generally – are not alien to capitalism is that, regardless of their immediate causes, these conflicts all get capitalized. As we explain theoretically and illustrate empirically below, these conflicts are continuously appropriated by and integrated into the very logic of capitalized power. And once discounted, they become part of capital itself.

2. The Capitalization of Power

To see how conflict gets capitalized and what it means, it is useful to backtrack a bit. In our work, we have argued that hierarchical societies are best understood not as modes of production and consumption, but as conflictual modes of power (Nitzan and Bichler 2009).

The first mode of power – that of the ancient empires – emerged in Mesopotamia and Egypt in the fourth millennium BCE. It rested on a triangular hierarchy of palace-army-church whose subjects were organized mostly via slavery and other forms of submission.

The subsequent mode of power – the feudal regimes of Europe, Africa and Japan – retained the hierarchical primacy of nobles-warriors-priests, but replaced outright slavery with personal bondage, fealty and servitude.

Capitalism, too, is a mode of power, but the nature of its power is fundamentally different than that of its predecessors. [5] In earlier regimes, power was conceived ontologically (as a thing, like god, thunder, army), concretely (with distinct properties and abilities) and personally (for example, by linking subjects to particular kings, nobles and clerics), and usually it was inflexible and changed only slowly. By contrast, capitalist power is operational, abstract, universal, highly dynamic and able to absorb and internalize other forms of power.

Let us flesh out these differences more concretely. The key symbol of capitalist power, we claim, is differential capitalization. Every social entity – a person, an owner, a corporation, a government, an NGO, a criminal organization, a religious outfit, etc. – can be capitalized. Reduced to its essentials, capitalization represents the discounting to present value of the entity’s risk-adjusted expected future earnings, as shown in Equation 1:

1. ![]()

In this equation, K is capitalization

(expressed in $); E is the future flow of earnings ($/time); H is

the excessive optimism/pessimism, or hype, that investors exhibit toward those future

earnings (a decimal ranging from ![]() to

to ![]() ); δ is the

risk associated with those future earnings (a positive decimal) and nrr

is the normal rate of return that investors expect to obtain under average

circumstances (a positive decimal/time).

); δ is the

risk associated with those future earnings (a positive decimal) and nrr

is the normal rate of return that investors expect to obtain under average

circumstances (a positive decimal/time).

For example, if the entity’s future flow of earnings E=$1 billion/year; investors are overly optimistic about these earnings, with hype H=2; the risk they associate with these future earnings is δ=4; and the normal rate of return nrr=0.1/year – then the entity’s capitalization is $5 billion:

2. ![]()

Building on Equation 1, the

entity’s differential capitalization ![]() is the ratio between its

own capitalization and the capitalization of some benchmark (consisting of another

entity – for example, another owner or corporation – or an index representing a

group of entities, like the S&P 500).

is the ratio between its

own capitalization and the capitalization of some benchmark (consisting of another

entity – for example, another owner or corporation – or an index representing a

group of entities, like the S&P 500).

Equation 3 shows this differential, with the subscript d denoting that the variable expresses the ratio between the value for the entity and the corresponding value for the benchmark (note that the normal rate of return is common to both the entity and its benchmark and therefore drops from the equation; for details, see Nitzan and Bichler 2009: Part III). All elements of Equation 3 are pure numbers, having no associated units.

3. ![]()

In our work, we argue and demonstrate that the basic components, or ‘elementary particles’, of capitalization – namely, future earnings, hype, risk and the normal rate of return – all hinge on power, and only power. And since the differential capitalization of any given entity is measured relative to a benchmark, its magnitude represents the entity’s power relative to that benchmark. This is where our notion of ‘capitalized power’ comes from.

Furthermore, we claim that the major driving force in capitalism is the compulsion to ‘beat the average’ and exceed the normal rate of return. And since, in capitalism, the ultimate variable of interest is the magnitude and rate of growth of capital – i.e., of capitalization – it follows that the final goal of all corporations and their owners is ‘differential accumulation’. They are all driven, relentlessly, to increase their differential capitalization relative to others.

What are the key features of differential-capitalization-as-power? For our purpose here, we highlight five.

First, differential capitalization is an operational symbol, an algorithmic ritual that conditions societal thinking and action more effectively and more thoroughly than any supreme-God church ever did. [6] Knowingly or not, all capitalist entities and their subjects abide by the dictates of differential capitalization. Anyone who invests, saves, borrows, lends, computes costs and benefits, designs a production process, makes policy, goes to war or decides on peace engages and aligns with, in one way or another, the capitalization ritual and its differentials.

Second, differential capitalization is entirely abstract, represented by a pure number (a ratio of two monetary magnitudes). This abstraction makes the capitalized power of any entity or group of entities comparable to the capitalized power of any other entity or group of entities. And this commensurability means that all measures of differential capitalization as power can be readily weighed, linked and aggregated.

Third, differential capitalization is universal, applicable anywhere and everywhere in the capitalist cosmos. This universality makes the accumulation of capital as power inherently boundaryless. [7]

Fourth, differential capitalization is highly dynamic, constantly changing in line with shifting circumstances and expectations. This dynamism enables capitalism to survive and even prosper through ongoing turbulence and repeated crises.

Fifth, and perhaps most importantly for our argument here, differential capitalization is highly absorptive: it shapes, appropriates an eventually integrates into itself almost every other form of power.

This latter feature is historically unprecedented. Earlier symbols of power tended to stand on their own, independently of and usually incommensurably with other symbols of power. For example, the might of a certain god was qualitatively different from and shared no common denominator with the size of a king’s army, or the number of an empire’s subjects. There was no obvious way to compare let alone aggregate them.

Not so with capitalized power. Here, every form of power perceived to affect the future earnings of a particular entity, the hype about those future earnings and their associated risk, gets discounted; whatever gets discounted is part of capitalization, by definition; and once capitalized, it is baked in the cake, having become a constituent portion of the entity’s differential-capitalization-as-power.

This latter feature allows capitalized power to internalize and embody not only so-called ‘economic’ forms of power, but potentially every form of power. The power of a corporation or group of corporations to use intellectual property rights to exclude rivals from a particular technology or commodity, to increase prices faster or lower them more slowly than others, to constrain labour costs more effectively, to obtain exclusive government contracts, to differentially shape tax policy, to hype investors about their relative prospects, etc., all get differentially capitalized as a matter of course. But ‘non-economic’ forms of power are routinely discounted as well. These include, among others, differential power over aspects of education, advertising and other forms of conditioning, environmental destruction, pollution, corruption, crime management and mismanagement, resource depletion, energy security, cultural redirection, access to food, hunger and healthcare. [8]

Now, violent hostilities and wars – including those driven by supreme-God churches – are no different than other processes of power: if they bear on differential future profitability, relative investors’ hype and/or differential risk, they get discounted and capitalized; and the moment they are capitalized, they become part of capital. In this sense, the current church-bound war in Gaza – insofar as it impacts these elementary particles – is part and parcel of the accumulation of capital as power.

3. Energy Conflicts and the Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition

Our previous work on the Middle East examined the discounting of organized violence and war into the global differential accumulation of dominant capital groups. Specifically, we showed how the differential profits and incomes of the ‘Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition’ – a group comprising large armament contractors, oil firms, OPEC, financial institutions and construction companies – were tightly correlated with, as well as helped predict, the cyclical eruption of ‘energy conflicts’ (Bichler and Nitzan 1996, 2015, 2018a, 2023; Nitzan and Bichler 1995, 2009).

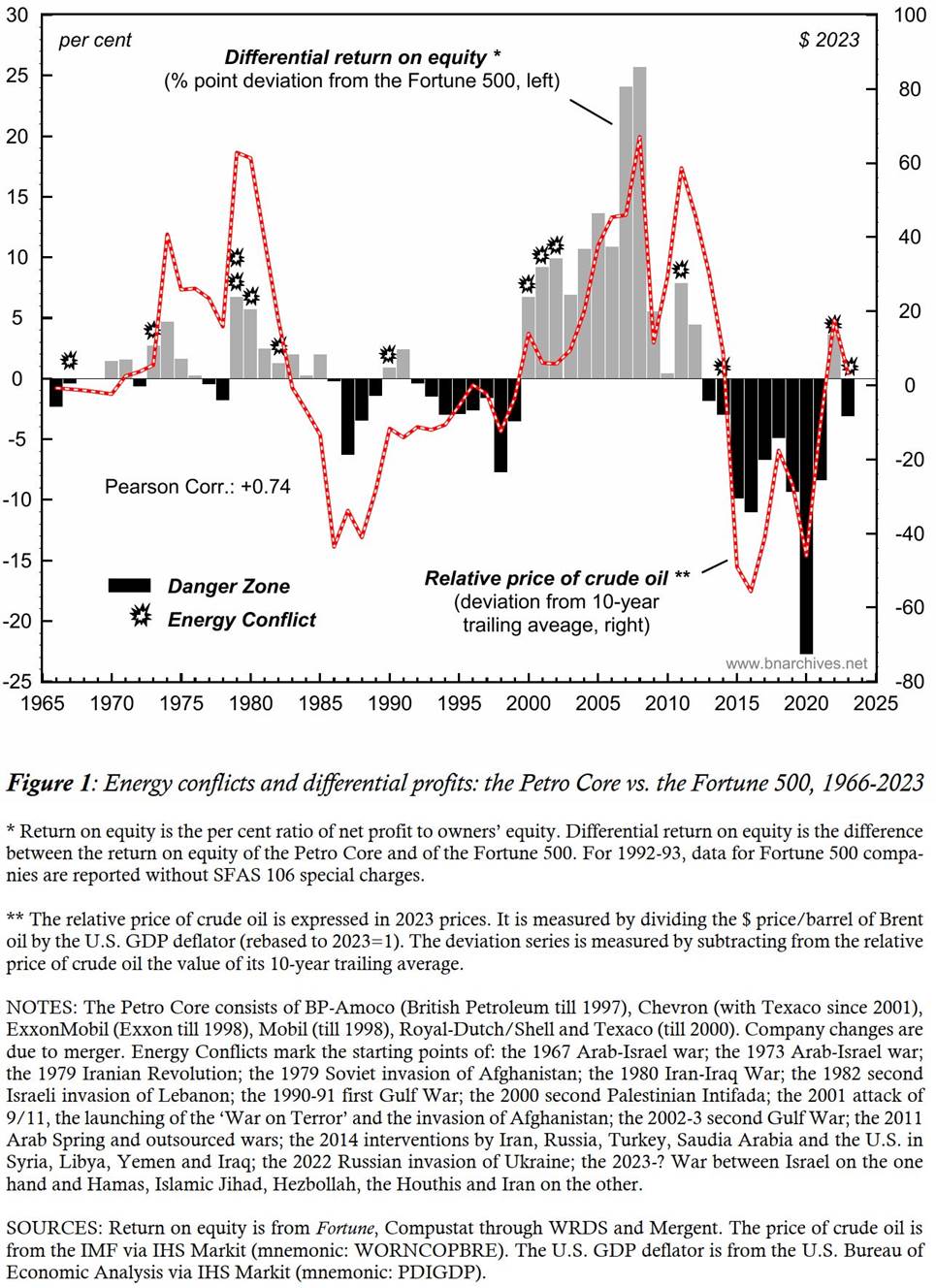

Figure 1, covering the period from the mid-1960s to 2023, illustrates this process with respect to oil.

The chart juxtaposes the movements of two distinct variables. The first variable, shown by the bars plotted against the left scale, pertains to the ‘Petro Core’ of leading listed oil companies (enumerated in the figure’s notes). The bars depict the differential return on equity of this Petro Core relative to the average return on equity of the Fortune 500. The differential itself is calculated in two steps: first, by computing the per cent ratio of net profit to owners’ equity for both the Petro Core and the Fortune 500; and second, by subtracting the latter from the former. If the difference is positive (grey bars), it means that the Petro Core beats the average with a higher return on equity. If it is negative (black bars), it implies that the Petro Core trails the average, with a lower return on equity. The movement of this differential, we argue, proxies changes in the capitalized power of the large oil companies relative to dominant capital as a whole: the larger/lower the measure, the greater/lesser the power. [9]

The dashed red series, shown against the right scale, is the change in the relative price of crude oil. This measure, too, is calculated in two steps: first, by dividing the dollar price per barrel of Brent oil by the U.S. GDP deflator (rebased to 2023=1); and second, by subtracting from this result its 10-year trailing average. The magnitude of this series, expressed in 2023 U.S. dollars, represents the ups and downs in the pricing power of the oil companies (and OPEC) relative to the pricing power of all U.S. sellers. [10]

The comparison reveals two important patterns. First, the two variables move tightly together, with a Pearson Correlation coefficient of +0.74 out of a maximum of 1. [11] In other words, the differential-return-on-equity-read-power of the large oil companies hinges mostly on their ability to raise oil prices faster (or lower them more slowly) than other corporations raise (lower) their own.

Second, as we show below, relative oil prices and differential oil returns both hinge on – and in turn predict – Middle East ‘energy conflicts’. The eruption of each energy conflict is depicted in the figure by an explosion sign (and identified in the notes underneath the figure). And as the data indicate, these conflicts tend to be preceded by a stretch of negative differential returns. We call these stretches danger zones, because they indicate that a new energy conflict is likely.

And here there arise three remarkable regularities.

First, and most importantly, every energy conflict save one was preceded by the Petro Core trailing the average. In other words, generally, for a Middle East energy conflict to erupt, the leading oil companies first must differentially decumulate. [12] The only apparent exception to this rule is the 2011 burst of the Arab Spring and the subsequent blooming of outsourced militia wars in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq – conflicts that were financed and supported by a multitude of governments, NGOs and supreme-God churches in and outside the region. The 2011 round erupted without a prior danger zone – although the Petro Core was very close to falling below the average. In 2010, its differential return on equity dropped to a razor-thin 0.4 per cent, down from around 25 per cent in both 2008 and 2009. (The 2023 war in Gaza, although preceded by a mini oil boom associated with Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, comes after a very long streak of massive differential oil losses.)

Second, every energy conflict, with one exception – the multiple interventions in 2014 – was followed by the oil companies beating the average. In other words, war and conflict in the region – processes that customarily are blamed for rattling, distorting and undermining the aggregate economy – have served the differential interest of the large oil companies (and OPEC) at the expense of leading non-oil firms (and countries). [13] This finding, however striking, should not surprise us. As Figure 1 shows, differential oil profits is intimately correlated with the relative price of oil; the relative price of oil in turn is highly responsive to Middle East risk perceptions, real or imaginary; these risk perceptions tend to jump in preparation for and during armed conflict; and as risks mount, they raise the relative price of oil and therefore the differential profits of the oil companies and the relative export revenues of OPEC.

Third and finally, according to our data, the Petro Core never managed to beat the average without a preceding energy conflict. In other words, the differential performance of the oil companies depends not on production, but on the most extreme exercise of power and sabotage: war.

Now, getting back to the theme of our paper, we can say that, if our analysis is valid – that is, if the ups and downs of relative oil prices, differential oil profits and OPEC’s oil revenues are largely the consequences of regional conflicts and war – it follows that these energy conflicts, along with those who propel, participate in them and suffer their consequences as bystanders, are all embedded in the differential-capitalization-as-power of the petroleum companies and OPEC. They all flicker in the market tickers of the oil companies and exporting countries.

4. Holy Conflicts for Differential Profits

Considering the regularities shown in Figure 1, the recent decade was truly exceptional. During the 2010s, the Petro Core sustained its biggest losses ever, while OPEC saw its oil revenues, expressed in per capita terms, roll back to their level half a century earlier (Bichler and Nitzan 2023: Figure 1). This was the picture in absolute, constant-dollar terms.

In differential terms – which is the measure capitalists, state officials and NGO leaders revere the most – the situation was equally bad, if not worse. As Figure 1 shows, beginning in 2013, the Petro Core trailed the average with unprecedented differential losses that even the multiple state and militia conflicts of 2014 failed to alleviate, let alone arrest. On the face of it, this inability to pull itself out of the danger zone suggested that the Petro Core was withering away, unable to rejuvenate its profits, not to mention lead the dominant-capital pack.

But existential crises often tease unity out of division – in this case, unity between the rulers of the losing companies, countries and associated militias. And indeed, when all seemed lost, the oil market finally started smelling the sweet scent of war. In 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, setting off a protracted conflict with multiple militia forces on both sides. And a year later, Hamas and Islamic Jihad attacked Israel, tiggering another bitter conflict with equally resolute militias on both sides.

So far, though, the differential oil results remain disappointing. In 2022, relative oil prices, oil profits and OPEC’s export earnings all zoomed. But the uptick was short lived. In 2023, the two wars, although intense and heavy in casualties, seemed insufficient to prop or even sustain those differentials. And with the Middle East again in a ‘danger zone’, the prospect is for more holy conflicts for the glory of differential profits.

Endnotes

[1] Bichler teaches political economy at colleges and universities in Israel. Jonathan Nitzan is an emeritus professor of political economy at York University in Canada. All their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (https://bnarchives.net). Work on this paper was partly supported by SSHRC.

[2] Steven Pressfield’s thriller, The Profession (2012), describers a not-so-distant future, in which giant mercenary armies complement and cooperate with traditional national armies by offering services to both corporations and states, including illegal and politically incorrect activities that nation-states prefer to avoid. Gradually, these mercenary armies alter the nature not only of international relations, but of the nation-state itself.

[3] Russian supported militias – like the Wagner Group and Chechen forces – operate in Syria, Africa and Ukraine, often against an array of enemy militias. The United States and its allies have used corporate mercenaries in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. Wahhabi militias police the Saudi population, ISIS operates in Iraq and Syria, while the Taliban rules Afghanistan. The United States supports Kurdish militias in and around Kurdistan, the Houthis rule much of Yemen, and Rabbinate settler militias increasingly stir Israel’s internal affairs and military adventures. The Saudis and various Gulf states support the Palestinian Hamas, while Iran backs the Islamic Jihad and Hezbollah in Palestine, Lebanon and Syria. Various Islamic groups control parts of Nigeria, Libya, Sudan and Somalia, among other countries, while organized crime gangs, engaged mostly in raw materials and drugs, are prevalent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Libya, Mexico, Colombia and Southeast Asia, often with global tentacles.

[4] We refer to the ‘supreme-God churches’ rather than to the ‘monotheistic religions’, mostly because our focus is not the belief of their followers but the hierarchical structures that impose these beliefs. As we explain in ‘The Road to Gaza’, all supreme-God churches are characterized, among other features, by their god’s insistence on and fight for exclusivity, hence the attribute ‘supreme’.

[5] It is worth noting that liberal ideology expunges power from capitalism proper. ‘True’ capitalism, it argues, comprises markets where economic power is constantly decimated by competition, and democratic politics where political power is regularly reset by elections. According to this view, actual power in capitalism, if and when it exists, is an exogenous distortion.

[6] For symbolism in general and the relation between operational symbols and capitalization in particular, see Martin (2019).

[7] Our reference here is to the abstract nature of differential accumulation. Its concrete features, being all and only about power, are crisscrossed with boundaries.

[8] For a systematic review of capital-as-power analyses of these and similar processes, see Bichler and Nitzan (2018b). For later contributions, visit The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (https://bnarchives.net) and Capital as Power (https://capitalaspower.com).

[9] We say ‘proxies’, first, since, mathematically, the differential return on equity is not identical to differential capitalization; and second, because the Fortune 500 is not a global benchmark: it includes only U.S.-based corporations, while excluding those based in other countries.

[10] For comparable charts with somewhat different corporate groupings, alternative measures for the variables and different time periods and frequencies, see Bichler and Nitzan (2015: Figure 5; 2023: Figure 2).

[11] This annual correlation is practically the same as the monthly one between the differential earnings per share of global integrated oil companies (relative to all listed firms in the world) and the relative price of crude oil (Bichler and Nitzan 2023: Figure 3).

[12] In the late 1970s and early 1980s, and again during the 2000s, differential decumulation was sometimes followed by a string of conflicts stretching over several years. In these instances, the result was a longer time lag between the initial spell of differential decumulation and some of the subsequent conflicts.

[13] A key point to note here is the effect of energy conflicts not on absolute but differential oil returns. For example, in 1969-1970, 1975, 1980-1982, 1985, 1991, 2001-2002, 2006-2007, 2009 and 2012, the rate of return on equity of the Petro Core fell; but in all cases the fall was either slower than that of the Fortune 500 or too small to close the positive gap between them, so despite the absolute decline, the Petro Core continued to beat the average.

References

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 1996. Putting the State In Its Place: US Foreign Policy and Differential Accumulation in Middle-East "Energy Conflicts". Review of International Political Economy 3 (4): 608-661.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2015. Still About Oil? Real-World Economics Review (70, February): 49-79.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2018a. Arms and Oil in the Middle East: A Biography of Research. Rethinking Marxism 30 (3): 418-440.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2018b. The CasP Project: Past, Present, Future. Review of Capital as Power 1 (3, April): 1-39.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2023. Blood and Oil in the Orient: A 2023 Update. Real-World Economics Review Blog, November 10.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2024. The Road to Gaza. Working Papers on Capital as Power (2024/01, August): 1-19.

Fix, Blair. 2022. Have We Passed Peak Capitalism? Real-World Economics Review (102, December): 55-88.

Martin, Ulf. 2019. The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery. Review of Capital as Power 1 (4, May): 1-30.

Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. 1995. Bringing Capital Accumulation Back In: The Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition -- Military Contractors, Oil Companies and Middle-East "Energy Conflicts". Review of International Political Economy 2 (3): 446-515.

Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. 2009. Capital as Power. A Study of Order and Creorder. RIPE Series in Global Political Economy. New York and London: Routledge.

Pressfield, Steven. 2012. The Profession. A Thriller. 1st ed. New York: Crown.